A POST-COLONIAL HISTORY OF PSYCHEDELIC TRANCE

Countercultural freaks built a hippie utopia in Goa, India—but for who?

This article first appeared in the March 2020 issue of DJ Mag, and has never appeared online. I’m sharing it for paid subscribers as an addendum to my dispatch from Ozora festival, a psychedelic tribal gathering in Hungary. As I wrote earlier, there has been a recent wave of revisionist history around genres like Detroit techno—with a growing awareness of the class privilege, misogyny, and other tensions inherent in these pioneering scenes’ formations. Far less attention has been paid to Goa trance, an equally important sound that drew heavily from India and romanticized notions of the East.

This essay aims to decolonize the story of a highly misunderstood yet influential genre by centering the experiences of local Indians; reframing the socio-cultural conditions the genre sprang from; and looking ahead at its resurgence in Asia’s contemporary party scenes.

A way to envision the sounds of our dystopian future is through the trippiest chapter of our rave history. Psychedelic trance, or psytrance, is making its revival as the soundtrack of our transnational, psychedelic age. The hyper-kinetic sound has been creeping into mainstream Western dance music: landmark festivals like Glastonbury have hosted psytrance stages, while DJs from Brooklyn to Berlin have been weaving the music into their sets.

With its pulsating kick drums and twisting synth lines, played at warp speeds of 135 to 200BPM, psytrance is the sonic embodiment of an LSD trip. It’s often augmented by the use of science fiction soundscapes and minor blues scales, as well as pitch-bending techniques and complex layers of instrumentation.

This sense of disorientation is key to psytrance’s sonic evolution, alongside a counterculture of psychedelic drugs used by nomadic hippies, who began flocking to Goa, India in the late-1960s in search of alternative ways of being. As Goa’s beach raves were replicated and commodified overseas, the genre grew into a global party culture — massive contemporary festivals like Rainbow Serpent in Australia and Boom in Portugal can draw up to 40,000 ravers.

Fusing psychedelic drugs with New Age spirituality, environmentalism, technology, self-discovery and escapism — arguably, psytrance is a subculture attuned to the resonances of today’s world. Yet, compared to the origin stories of other seminal electronic music genres, like acid house in Ibiza and techno in Detroit, psytrance — and its appropriation of Indian cultural and spiritual practices — remains somewhat under-historicised, and the white supremacy, orientalism and exoticism that’s part of it history is rarely discussed in-depth, or even avoided.

In the spirit of larger conversations around race and music, perhaps it’s time to decolonize the story of psychedelic trance: to understand the true impact of this misunderstood yet influential genre.

THE TRIPPY ORIGINS OF PSYCHEDELIC TRANCE

Psychedelic trance was born in Goa, an island and former Portuguese colony 600km south of Mumbai that is India’s smallest state. Starting in the late 1960s, it became a popular stop on the “hippie trail,” a travel route that connected European countries to places in the Middle East and Asia where you could obtain an immensely popular psychedelic: cannabis.

At the time, there was a strong Western interest in the spiritual practices of India, where cannabis was legal until the 1970s. Goa’s abundance of hashish, a concentrated form of cannabis, made it popular amongst these hippies; according to Arun Saldanha’s Psychedelic White: Goa Trance and the Viscosity of Race, many travelers saw the island as “less Indian” because of its Portuguese colonial history, and perceived the locals to be more “socially tolerant”. Goa’s Anjuna beach became a hotspot in part because it didn’t have a police station, so foreigners could openly do drugs without having to pay ‘baksheesh’, or bribes.

Goa Gil, a Californian, is considered the godfather of psytrance. He arrived in Goa as an 18-year-old, fresh from San Francisco’s hippie scene. When the scene started deteriorating into violence and hard drugs after the summer of ’69, Gil decided to go on his own “world dope tour,” with Goa as his final stop. “The first parties were mostly campfires at the beach, with acoustic guitars and some drums,” recalls Gil, who answers our video call wrapped in flowing, saffron-coloured robes, a red dot of ash smudged on his broad, wrinkled forehead.

Perhaps more than any other figure, Gil embodies the intersection of Indian spiritualism and Western psychedelic culture that informs early psytrance. During a tour of Indian holy sites in ’69, he became a disciple to a guru and eventually earned the title of a Hindu ‘sadhu’, or holy man. Before he DJs, Gil sets up his ‘puja’, or temple ceremony, and says his mantras. To him, “It is not a disco under coconut trees: [psytrance parties] are a spiritual initiation,” he once said.

While this sort of practice might seem performative for, say, a white DJ at Burning Man, Gil’s decades of devotional training make his approach to rave spiritualism less easy to dismiss. “Music is a way to go into a trance, and a party is a vehicle to transmit ideas and knowledge,” he tells us. “I’ve always viewed parties as a platform to give people blessings. This is one of the ways that I worship the earth and the cosmic spirit.”

In the mid-’70s, Gil and his friends started building stages in the sand and performing psychedelic rock concerts, inspired by the Grateful Dead. He also cites Rough Trade, industrial hip-hop group Fats Comet, “heavy duty breaks,” British industrial band Portion Control, Belgian EBM group Front 242 and Psychic TV as early influences.

“Electronic music at that time was very new,” he says. “Some people recognised [that] and went with it. But the resistance was very strong in the beginning.” By the early-’80s, however, synthesizers had largely replaced electric guitars, and with the UK media’s sensationalist coverage of Goa’s hippie party scene, European DJs began flocking to the island, armed with tape decks and cassettes of early techno from labels like Germany’s ZYX Records.

Tracks were often mixed with the vocals cut out, allowing DJs to extend them into morphing grooves, and played on DAT tapes instead of vinyl. Goa’s tropical heat made mixing more difficult, so psytrance tracks were produced with layers of sound at the beginning and end, instead of a simple beat. “Nobody DJed with vinyl, how could you?” Gil chuckles. “Outside on the beach, if the wind blows, the needle just flies.”

By the ’90s, Goa trance had emerged from this mish-mash of styles — characterised by frenetic arpeggio patterns and basslines in “oriental patterns” using the Phrygian Major scale, along with samples of chanted Hindu mantras. This was all geared towards mind-expansion, or Gil puts it: “As [the music] gets faster, we evolve with that, and it’s increasing our ability to understand things.”

With the exception of an occasional atmospheric break, the musical structure moves in a repetitive weave of 4/4 motorik kick drums, a drone-like bass pattern, and pulse-rhythms of sixteenths in slippery textures that produce the “acid,” or psychedelic flavour, played at around 140–155 BPM.

“These psycho-acoustical tricks keep your brain interested and doing mental gymnastics that other music doesn’t do, because there are more traditional verse/chorus structures,” notes Ajja, a Swiss artist who grew up in Goa and is one of the biggest names in today’s psytrance scene. “Classical music does this beautifully, too. After a while, you stop thinking about it and just experience it. It talks to your body more than your brain.”

A HIPPIE UTOPIA — BUT FOR WHO?

From the get-go, psytrance was framed as being resistant to capitalist modernity. “Religion, rebirth, the Cold War, drugs, time travel, mysticism, nuclear disaster and sci-fi were all popular themes, and at times it felt like these messages were being beamed down directly from space,” writes Dave Mothersole in Unveiling The Secret: The Roots of Trance, who went to his first Goa party in ’86. “That we were God’s chosen ones, his disco dancing, cosmic flower children ecstatically gyrating our way, Shiva-like into new realms and understanding.”

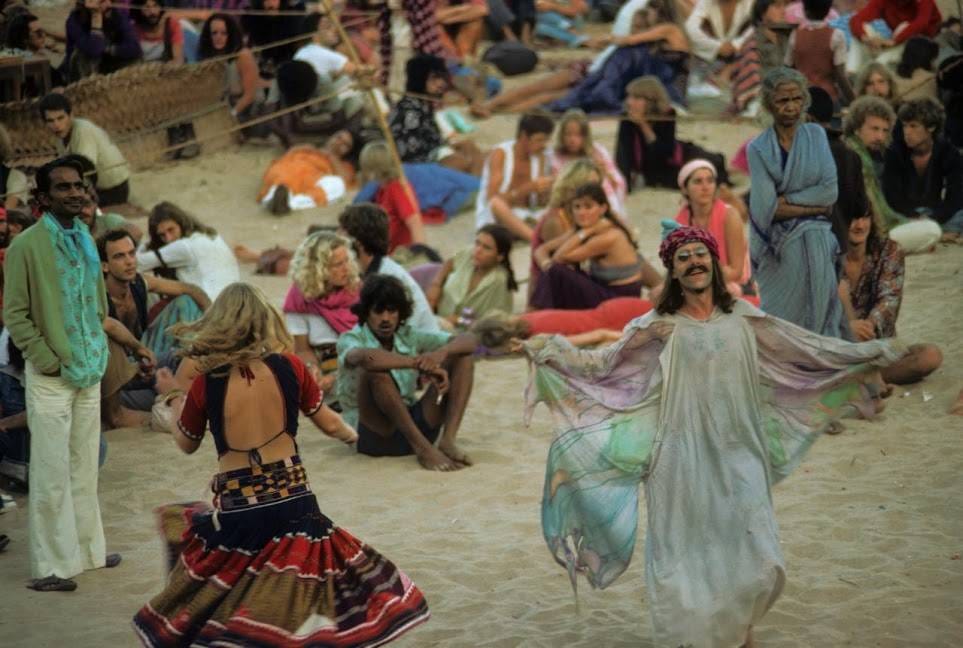

After taking a hit from his pipe, Gil says, “It started very small and underground. The Europeans — mostly Italians and French — didn’t want you to look at them. It was dark and weird. There were no photos on the dancefloor. If someone saw your camera they’d take it and throw it into the ocean. Then, in the ’90s, suddenly, there were all these people dressed up in bright colors. Like, look at me! It became a whole different vibe.”

At the same time, it’s impossible to look at photos from this era now and not see an ocean of overwhelmingly white kids, dressed in photoshoot-worthy alternative regalia. And while the local Goans were perceived by these hippies to be “socially tolerant”, in fact, many lived in conservative Catholics villages, while many others were devout Hindus. Their perspectives on the scene are sorely missing from historical records of this era. In a GQ magazine profile of Goa Gil, the journalist Kerry Harwin went to Goa and asked some old-timer ravers how the locals perceived their antics.

“There were very few [Indians] at that time [and]… They’d never seen anything like this,” said Walter, a 69-year-old Canadian who has been living in Goa for decades. “They’d go down to the sea and what would they find down there? All of a sudden these new aliens from outer space, naked all over the beach.”

When we ask if any local ravers were part of the early community, Gil says that their participation was mostly limited to providing the commercial infrastructure for these international ravers. “There was a whole scene of chai shops, where you’d sit with the local chai mamas who sold biscuits and food on the edge of the scene — and a few youngsters,” he says. Even though these white hippies came to Goa in search of an alternate, more liberated way of being, they often replicated the very systems of exclusion and oppression they were ostensibly escaping.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Rave New World to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.