NO WAY BACK 🌀

Sacred transmissions from a heavy acid zone

There is always a hesitation to blab about your favorite parties. An instinct to protect the sacred and shield it from those who do not Get It. No one wants to the idiot who lights the spark that blows it up. I find myself wrestling with this conundrum most acutely while documenting scenes that tend to shy away from the camera glare, torn between the desire to canonize an under-reported cultural history vs. protect the underground.

Back in the day, the paucity of public information channels meant that journalists often held the keys to the gates of the underworld. It was easier to point at canonical countercultural reportage—like Robert Gordon Wasson’s 1957 photo essay on “discovering” magic mushrooms in Life Magazine, or i-D magazine's 1995 trend piece on the Goa Trance scene—and be like, LOOK AT THESE ASSHOLES RUINING IT FOR THE REAL HEADS! The situation is messier these days, when everyone is giving away the secrets—for free!—on social media, filming themselves for the feed and finding loopholes in no-photo policies by snapping obligatory Berghain selfies. What’s the point of being precious about rave reporting when a party is more likely to go viral on TikTok?

For me, it comes down to paywalls and platforms. When I was writing for new media sites like VICE in the 2010s, the success schema of that era valorized virality—profits and infamy came from maximizing clicks, and winning the game often felt like taking dunks on Twitter and courting controversy at the expense of your mental health. But as the media landscape fractalizes into the current age of clearnet vs dark forest networks, it’s starting to feel possible to whisper again.

When Dancecult editor Graham St John reached out asking if I had ideas for the academic journal’s upcoming Psychedelics and Spirituality issue, I decided it was time. Time to contribute my little addendum to the legend of No Way Back—a party that slithers out of Detroit’s fertile soil once a year and is quite possibly the holy grail. For now, the vibe is still IYKYK, and the crew behind it have done precious few interviews (this RBMA Q&A is the best one).

No Way Back’s hidden gem status put it on the same wavelength as Dancecult—a peer-reviewed, open-access journal and research network about the deepest niches of electronic music and culture. Despite being around for the last 15 years, Dancecult remains largely a heads-and-nerds-only endeavor; its website is reminiscent of early internet forums in a no-frills way that’s delightfully endearing.

This current issue on Psychedelica and Electronica is full of the good shit—the kind of dense, pungent compost that feeds mycelially-inclined minds. St. John, who is academia’s resident psytrance expert, analyzes how the popular practice of sampling Terrance McKenna’s voice in acid house and psytrance tracks has become a sort of “tryptameme” (as guest editor Trace Reddell put it). Independent researcher Georgia Gia writes about ketamine and anarchy at Mutonia, an autonomous zone in Italy whose Max Max-style metal sculptures formed the visual inspos for Spiral Tribe and other free tekno raves (and she has the SICK photos to prove it). Master light manipulator C. Scott Taylor tells the story of Spontinuity, a Colorado-based collective that bent many visual fields and minds for The Greatful Dead and other psychedelic acts in the 60s and 70s.

Below, my piece on No Way Back traces the party’s lineage to 90s Detroit’s psychedelia in order to understand why the vibe transmission is so damn strong. In addition to getting a veritable Detroit music history lesson from BMG and meeting Erika’s pet kitty, I particularly enjoyed talking to Amber Gillen about the aesthetics of the party, and how to properly create a comfortable visual landscape that doesn’t feel like you’re just stuck in the strobing, anxious come-up of a trip. I won’t say too much more except to thank Bryan and Graham for the trust. You can read the text below, or in its original form over at Dancecult.

There are raves that remind you what it is to be alive, and then there are the rest. You never know when a party will crack you open, but the secret sauce often includes these ingredients: DJs who weave ideas into tapestries of sound, hours long enough to bend the space-time continuum (12 hours is often the sweet spot); substances that encourage mind-expansion over tunnel vision; a collective desire to go deep. Raves aren’t easy. Sometimes they rip you up, spit you out, conjure demons. The muck lodged in your psyche gets unstuck, worked out and purged through the body. But then you break into the great beyond.

There is one party renowned in the dance music underground for reliably bestowing this deliverance. It is a party with a cult following so strong that we think of it as Techno Thanksgiving, a family reunion for the American rave scene. This party is also the contemporary torchbearer of the Detroit rave continuum, which stretches back to the very roots of rave history. This party is called No Way Back.

No Way Back is a heavy acid zone. The DJs who throw it are associated with the esteemed music labels Interdimensional Transmissions in Detroit and The Bunker in New York, and the tight-knit crew are acid house and techno freaks. The burbling squelch of the 303 is like a layer of oil that oozes out of the speakers from the moment the party begins at midnight and winds down in the afternoon. Wonky synthesizers that sound like the metallic wails of spaceships landing, the gurgling of machines being burped, the sizzle of brains frying. Slide around and hear it hiss.

At some point over its 16-year lifespan, it became a crucial part of No Way Back’s lore that it is an LSD party. Nobody talks about this explicitly; the organizers don’t go around dosing the punch or anything silly. It’s just a thing that is understood implicitly, and this unspoken endeavor to dive down the wormhole collectively creates a sort of psychedelic safe space to get really weird and wig out. “When you roll in, you can expect to be immersed into a world with one purpose—”, explained The Bunker DJ and producer Jasen Loveland, who passed away in 2021 but whose spirit remains embedded in the party, “—to make you lose your fucking mind”.

I have been attending No Way Back since 2016, and at the last one, I worried that the cultural forces currently turning global rave culture into a boring version of social media-saturated entertainment would not spare this party, despite everyone’s best intentions. Thankfully, I was wrong, and once again left with a sense of total spiritual realignment. So I reached out to the DJ crew to understand how No Way Back manages to reach a dancefloor consciousness of the highest order. There are almost no interviews or press about this party online, but after much cajoling, emailing and rescheduling, I finally got Bryan Kasenic, Brendan M Gillen (AKA BMG) and Erika—several key DJs in the No Way Back crew—on the phone.

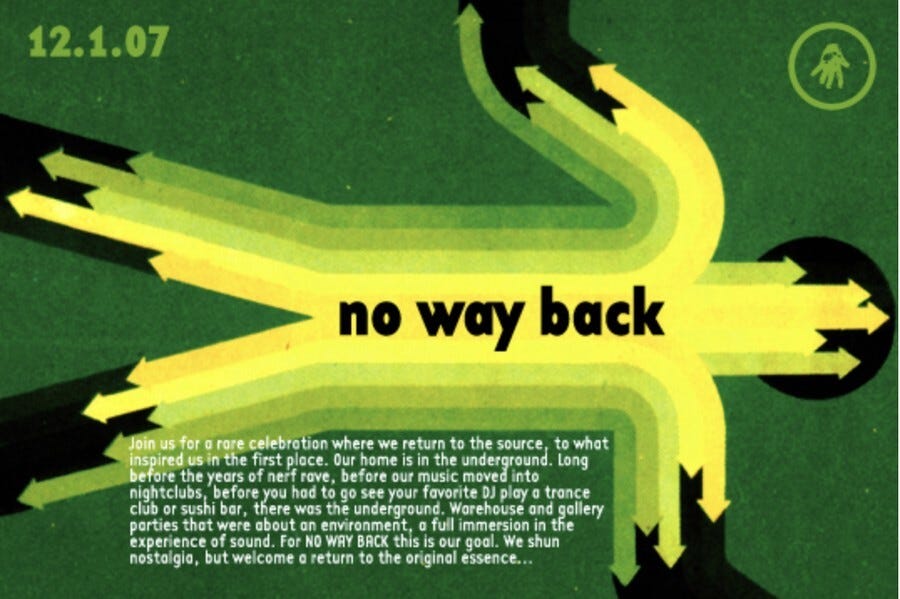

The first thing they did was point me towards the flier for the very First No Way Back (see Fig. 1) in Detroit in December 2007. Stated right there, in plain text against a mossy green background, was the party’s manifesto—a statement of intent that still holds true:

Join us for a rave celebration, where we return to the source, to what inspired us in the first place. Our home is in the underground. Long before the years of nerf rave, before our music moved into nightclubs, before you had to go see your favorite DJ play a trance club or sushi bar, there was an underground. Warehouse and gallery parties that were about an environment, a full immersion in the experience of sound. For NO WAY BACK this is our goal. We shun nostalgia, but welcome a return to the original essence.

Figure 1. No Way Back, first flier, 1997. Courtesy of No Way Back.

Detroit’s electronic music scene in the 2000s was experiencing a nadir, Gillen explained. In the late’90s, a media-fueled moral panic over ecstasy use had resulted in a nationwide crackdown on rave culture—and Detroit “clamped down hard”, according to a Red Bull Music Academy’s report, “Breaking up parties, writing tickets and occasionally even brutalizing ravers” (Glazer 2014). The actions of the police had a chilling effect on illegal warehouse party organizers, but new clubs, bars and other legal nightlife establishments began to take their place. These venues, however, had 2:00 AM closing times and revenue models based around alcohol sales.

“I was sick of going to parties and seeing the DJs right in front of a pool table, and looking at my reflection in a Coors sign. I just found that offensive”, said Gillen. “The Detroit rave scene in the’90s was anti-alcohol. We didn’t like what happened to people who drink all the time.” At now-legendary acid house parties at the Music Institute, or by legendary Detroit promoters like Dean Major and Analog Systems, punters danced all night to druggy anthems like “Jesus Loves the Acid” by Ecstasy Club and Garden of Eden’s “The Garden Of Eden”, often on just a $5 hit of LSD. “There was an open culture around it”, Gillen said. “People were transforming their lives, and this was a tool to get out of their normal boring jobs and become a really amazing creative person. It was a really fascinating time”.

No Way Back was thus conceived as a return to the source: the original ’90s Midwestern rave culture and its anarchic, psychedelic roots. Accordingly, the music played at the party reflects the soul of the city. “You can ask someone to play ‘psychedelic,’ and they might come in and play a really fast psytrance set,” Kasenic said. “I don’t know if there’s an objective way to define psychedelic music, but because the party is from Detroit, there’s so much emphasis on funk”.

“If you ask any Detroit house or techno artist what their inspirations are, George Clinton and Parliament-Funkadelic are going to come up”, added Gillen, noting that Maggot Brain, Funkadelic’s third studio album, was allegedly recorded while the band was heavily dosed on acid. This strain of Detroit psychedelia connects George Clinton to Richie Hawtin, a seminal figure of ’90s Detroit rave culture who, under his Plastikman moniker, released an album called Sheet 1 in a perforated cover that looked so much like acid tabs that a fan was arrested just for owning the release (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Cover of Plastikman, Sheet 1, 1993 (Novamute).

Aesthetically, one of the most distinctive features of No Way Back is the draping of beige parachutes over the dancefloor—a visual design that is especially friendly to trippers. “I wanted it to feel like a hug for the audience, with arms coming out towards you. When you lower the ceiling, people feel less exposed, like it’s a cave environment.” explained Amber Gillen, who designs the decor for the party. At established techno clubs like Berghain or Tresor, your visual experience is often predetermined by the in-house system of expensive lights and lasers—and these strobing, high-intensity configurations, as the No Way Back crew points out, can make you feel like you’re stuck in the heart-palpitating, anticipatory come-up phase of a trip.

The lighting at No Way Back is much gentler, thereby allowing psychedelics to provide individualized visual content instead. “The concept is a steady glowing and pulsing light that your frontal cortex can relax to, so you can zone out and feel comfortable in the space,” explained Amber. “It’s not flashing or moving too much. There’s also a lot of softer textures like drapery and netting to diffuse the lighting, and just symbols and shapes—no words or texts”.

All of these elements thus percolate into a perfectly calibrated psychedelic rave, and these are the reasons why No Way Back feels so alive. It is a party connected to both its local history and broader lineage: an acid-fueled Detroit rave tradition that harkens back to legendary clubs like New York’s Paradise Garage or the Muzic Box in Chicago—in other words, places where pleasures of the highest sense were attained through dancing out of your fucking mind on LSD. These experiences are harder to find these days. Parties get blown up on TikTok and meme’d into simulations of hedonism. The algorithm flattens and sucks out the dancefloor’s soul. But at least for now, there is a parachute-draped rave cave in Detroit that opens once a year, where you can walk out into the sunrise covered in sweat and dust, and feel like you’re touching the infinite.

THE DETROIT TECHNO TO LA HARDSTYLE CONTINUUM

I went to the most recent No Way Back with DJ Ty, who was inspired to make a mix that draws an unexpected throughline from Detroit techno to LA hardstyle (!!) for his Dublab radio show, The Long Decay. In fusing these two wildly different genres, Ty perceives“a kind of solidarity between frustrated cities full of disillusionment, something to fill the vacuum when utopianism is revealed a farce.”

Here’s a little more about what he had to say about it:

Several weeks ago, I had the privilege of visiting Detroit, Michigan for DEMF / the collective of parties that orbit around people in town for Movement Festival. Many of the sets I saw there have buried themselves so deeply in my brain that I’m only beginning to experience them as memories. In the mean time they had done a kind of shifting and exhalation through me, even while I was not cognizant of them, folding so elegantly into the fabric of reality as to seem completely continuous with it. But still there, exerting influence.

This is a letter about the recontextualization of influence. Returning to LA, my rhythmic brain kept grasping for tones and resonances in my town’s underground dance music palate that told a similar story. While LA didn’t invent techno—Detroit did—it did perfect its own brand of hard, driving dance music animated by similar impulses. Many different genres of music have reestablished themselves here, but few feel so boldly declarative and indigenous the way techno does to Detroit as hard house feels to LA.

I still think about that mix sometimes. Listen to it here, and have a fab weekend!

Hi Michelle, I really loved this piece - a history of music, parties/raves, subculture and drugs, littered with passages of subjective, ecstatic writing. Hope to see more of this, and even long-form versions.