Stickers skating in New York City (Photo by Matthew Beck @plasticlunch)

***

This is the real story behind one of the most dramatic events I reported on this summer: the kidnapping of a queer protestor named Stickers by the NYPD. I’ve been sitting on this essay for a few months, nervous to reveal such vulnerable intimacy. But last week, the latest episode of The Cut’s excellent podcast, ‘Protesting Without Rules,’ interviewed Stickers and I about the kidnapping, so I figured, fuck it—isn’t this newsletter supposed to take you behind the curtain of the official story? Isn’t the ~real tea~ exactly what we’re here for? So I sent my draft to Stickers and after removing a few details, here is her approved version. Some of ya’ll might frown at some of the indiscretions described below, but only the rave gods can judge us.

***

I arrived at New York’s autonomous zone Abolition Park one searing afternoon in July, and found it nearly deserted—everyone except for a few stragglers had absconded to the beach. Wandering around, I spotted a booth named “The People’s Smoke Spot,” decorated with illustrations of joints. I asked the girl behind the booth if they were giving away weed. “Nah,” she said with a grin, “But… we are taking donations!” In a goofy drawl she introduced herself as Stickers, I tossed her a doobie, and just like that, we became friends.

Over the next few weeks, I’d spot her cruising up to various protests on her skateboard, twin sheets of blonde hair flapping in the wind, joint dangling out of the corner of her mouth, no fucks given. Tall and lanky with runway cheekbones and the slouching gait of a skater, she stood out even amongst the cast of colorful characters hanging around the autonomous zone. Technically, I suppose she was homeless, but Stickers reminded me of a kid straight out of Kids—living fast and loose on the streets, catcalling strangers and flipping off cops, crashing wherever the night’s hijinks wound up. I didn’t know people like this still existed in New York.

Stickers at Abolition Park (Photo by Matthew Beck)

On the night Stickers was kidnapped, we were marching against the shutdown of Abolition Park. Following Mayor De Blasio’s orders, the NYPD had raided it a few days earlier, tearing down tents and dashing the grand plans we had to throw a protest rave. So everyone who’d become family in the zone reunited for a 24-hour march through the city, and we’d just spent the afternoon in Washington Square Park, eating empanadas and dancing to a boombox. Stickers jumped into the fountain and emerged soaking wet, throwing her hands up to Whitney Houston and proclaiming, “Ohhh, I wanna dance with somebody…”

After lunch we were marching down 28th street when suddenly everything flipped on a dime: an unmarked van screeched up to the frontline, as men jumped out and grabbed Stickers, while another cop car nearly plowed into the back of the group. Suddenly, everywhere, people were screaming and crying; as more hulking cops in riot gear surrounded us, one woman’s legs gave out and she collapsed to the ground, shaking uncontrollably.

Livestreaming this chaos, I eventually found myself on a street corner next to Madison Square Park as officers tackled protestors to the ground to arrest them. A protestor who I’ll call X came up to me and thrust their phone in my face to show me a video of the kidnapping. “Look,” they said, sobbing, “They got Stickers!” That’s when I realized the full horror of what had happened. “Send me that video,” I said, stomach twisting. “We’ve got to get the word out.”

You probably know what happened next: my tweet of the video, originally shot by journalist Brandon English, went insanely viral and helped propel Stickers’ kidnapping to the front page of the New York Times and all over cable news. First Portland, now New York—the internet freaked that even America’s most liberal cities weren’t safe from gestapo tactics. Stickers was released later that night, and a GoFundMe ended up raising over $45,000 to help her find housing. A few weeks later, I reached out, wanting to hear her side of the incident before I left New York.

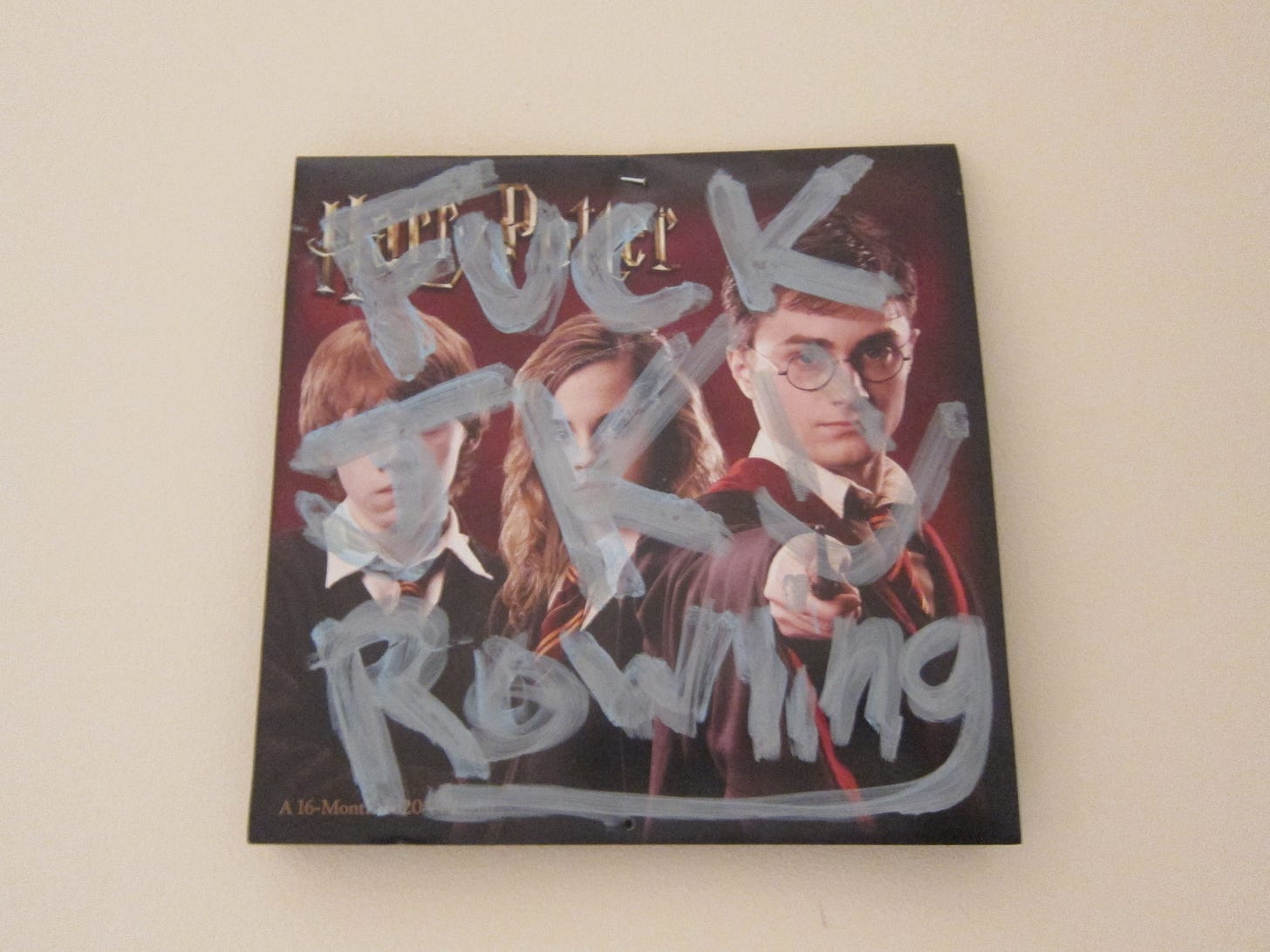

She invited me to her new crib in Washington Heights. She’d just moved in earlier that day. The walls of her room were covered in momentos she’d swiped from the subway—a Christopher Street station plaque, a sticker of the 1 train’s route—as well as a sign that said ‘FUCK JK ROWLING.’ We hit the bong, and she started to tell me her story.

Stickers in her room (Photos from this point are by me)

Stickers discovered the autonomous zone by accident. She was skateboarding at Washington Square Park when she started chatting with some kids who were spray painting and writing political slogans on the ground with chalk. They took her to Abolition Park, and she ended up staying for a week. “I didn’t know I would spend the night, but the energy was so great,” she said. “I had some of the best days of my life there.” Stickers, who is trans, said the zone was the only place where she felt truly accepted. “I get treated like a freak everywhere else, but there, I got so much love and support,” she said. “One of the first things I was asked was ‘what are your pronouns?’ That’s not something I get asked on the regular.”

Stickers was legally separated from her family at eight years old, and grew up floating through the Child Protection Service system, living in psych hospitals for months at a time because she had nowhere else to go. “Residential treatment centers wouldn’t take me because I refused to stay and behave anywhere,” she said. “Because of that, I’ve faced a lot of abuse throughout my childhood. But I’ve grown and kind of accepted that it happened, and kind of healed.”

“I was tripping on shrooms the night [the autonomous zone] got shut down,” she continued with a guffaw. “We had a huge meeting because we suspected the cops were going to raid. When 3:30am struck, 300 cops came in full riot gear, just to get 30 fucking commies out of the space. It was one of the most terrifying things I’ve ever experienced—I still get anxiety over the sound of whistles and metal barricades dragging.”

Here’s what Stickers remembers from the kidnapping:

I was on the front lines holding down traffic, and I ended up spotting this Kia. I was like, yo guys watch out that’s a cop. I don’t think they expected to arrest me right then and there, but I genuinely blew their cover. I pushed my skateboard away because it can be used as evidence of riot shields or whatever, and they finally got me in cuffs after 10 minutes. While I was in the van, the cops were shoving my face, putting their knees in my back, and pounding my head into the back seat. I had an anxiety attack. They told me to ‘act like a fucking human and not like an animal,’ which is weird because a fight-or-flight is a human response. They were like, “there are cameras in the car.” And I was freaking out, screaming “I LOVE CAMERAS!”

They never used my preferred name—they dead-named me, and when that happens, I just shut down. I was also never shown a warrant approved by a judge.

I was put in a cell, then went to the detective’s floor and was put in an interview room for an hour or two. They came in and tried to show me pictures of people I “didn’t know.” I just bitched at them, like, “The fuck are you all doing bringing these pictures of these random fucking people to me? I was fucking beat in a car, and you expect me to be compliant?” I just told them to fuck off! They left me in there for hours, then finally read me my rights, and made me sign papers before they released me.

Stickers pointed out that the police use unmarked vehicles to make arrests all the time. “Maybe it’s because I’m white,” she said. “No one sees that this happens to so many other people besides me.” She’s right—plainclothes officers, often referred to as “jump out boys,” often use this tactic in black and brown neighborhoods in cities around the country. “It’s a terrifying vehicle for racial profiling in many circumstances,” said Carl Takei, a senior staff attorney at the ACLU, to Courier. In August, a similar arrest happened in Kenosha, Washington, when plainclothes officers pointed a gun, smashed a car window, and dragged Riot Kitchen volunteers out of a vehicle to arrest them.

The NYPD’s official reason for Stickers’ kidnapping was that she had been spray painting police cameras around the autonomous zone. “I never thought I would get grabbed up in an unmarked van by officers who beat me and stood on top of me in a van,” Stickers said. “It’s just vandalism—it happens every day.”

After her kidnapping went viral, Stickers struggled with the barrage of attention she got online. “I don’t ever want to be famous, and I was on every fucking news channel for two weeks,” she said. “I’ve had my fair share of hate, but I’ve never been exposed to hate like this—it was so strong that I didn’t know what to do with it.”

She sighed and packed another bowl. I hit it, then flopped belly first in her bed, shutting off my recorder. Suddenly she was lying on top of me, nuzzling against my shoulder. She smelled like bubblegum and sweat. I turned around to face her—and just like, we became lovers.

At first, I was hesitant to hook up with a source—a nightlife reporter lives in sin, but this is a line I’ve never crossed. But she seduced me with a barrage of stoner memes over the next week, and on my last night in New York, I’m sitting on a bench on the Lower East Side when she texted me: what are you doing? I’m exploring the subway tunnels. I gawked at my phone. New York’s underground tunnel network is a mysterious frontier I’ve never been able to access—it requires someone who knows how to sneak in, and due to a lack of connections in the graffiti scene, I’ve never had a Virgil-type guide. Now, this was my chance.

So we linked up and ran down Canal Street holding hands, clambering down the subway station stairs and ducking underneath the DO NOT CROSS tape, down a ladder and into the dark tunnel, heart pounding. Every time I got spooked that a train was approaching, she would coo, “I got you,” telling me that she often came down here alone. We eventually wound up at the abandoned subway station underneath City Hall, which was built in 1902 and covered in a majestic mosaic of tiles and chandeliers, like the forgotten cousin of Grand Central. Above us was the plaza where the autonomous zone once stood—somehow, our journey had come full circle, like the universe winking. We fucked in the middle the subway tracks, carefully avoiding the third rail. Afterwards, she gave me a high-five: “that was epic!” Hours later we emerged back above ground, covered in soot, giggling.

New York often felt like a well-worn cliché whenever I returned, every street choked with ghosts, every night unfolding like a soap opera rerun. But as we cruised back to Brooklyn, Stickers pointed out funny graffiti tags and told me stories of the skaters behind them, showing me a face of the city that had always eluded my vision. The streets became an obstacle course—every subway turnstile to be hopped over, every bathroom a space to roll a joint, even the towering Williamsburg bridge was just a smoking perch to be climbed. In Stickers’ world, a wilder New York became legible—hidden from the yuppies who fled the city during the pandemic, it feels inchoate yet nostalgic, and most of all, unpredictable again. The city no longer felt like a dead end.

The next morning was shrouded in a cold, grey drizzle. Things were moving too quickly to savor saying goodbye, and anyway we were both stoned and I was late to the airport as usual. All I remember is her putting my bags in the car, and then giving her a rushed kiss in the rain. She waved goodbye through the tinted window, and then I’m gone.

RAVE NEW WORLD IN THE NEWZ

Ayyy, RNW gone some shine in the mediaverse last week!

The alt-media collective Study Hall interviewed me about Rave New World! I shared some thoughts on navigating autonomous zones, including issues of objectivity and privacy. I really love how writer Adam Willems described this project:

“Rave New World is a study of contemporary political movements in the United States, and positions pleasure and partying as tools for revolution… to Lhooq, both raves and recent autonomous zones are temporary, site-specific instantiations of abolitionist models of community.”

The Cut just released a new pod called Protesting Without Rules, which distills some reporting I’ve done on “Protestchella” and the politics of pleasure. When the spunky host Avery Trufelman pulled up to my friend’s backyard in Bushwick with a mic and asked me to tell her about my summer, I had no idea what to expect—two months later, it was really cool to hear my reporting refracted through this portrait of today’s protest culture.

Avery also spoke with Stickers, an NYPD detective, and Gen Z activists while tackling a tricky question: is there a “right” way to protest in 2020?