I recently dropped a piece in the Guardian about how the proliferation of both Narcan and test strips in underground party spaces underscores a broader shift in attitudes—and aesthetics—around harm reduction, a public health philosophy that is moving from the fringes to the center of the cultural zeitgeist. I started noticing this phenomenon last year as I ran around New York and LA writing about the reopening of nightlife: harm reduction is becoming cool, and when I say “cool” I don’t mean that in a stupid, superficial way (although I’ve heard of TikTok influencers copping Narcan for clout!), but in a real way—one that’s based on self and community care.

To understand how the harm reduction movement has arrived at this moment, I spoke to everyone from DJs to underground organizers to New York’s Nightlife Mayor. Along the way, I discovered a sick new print magazine called Dirty, which was started by a bunch of downtown New York street kids, artists, and skaters about a year ago—and is making harm reduction part of its core mission.

Dirty gives me the feeling of flying down Orchard Street from East Houston to Canal, high as fuck, hot air from the subway grates in my hair and no one expecting me nowhere. It’s a very specific Lower East Side vibe, with a sort of street grit that can feel missing from the Dimes Square/Red Scare/Drunken Canal scene that dominates the mainstream media’s portrayal of today’s downtown New York.

When I called Dirty’s editor-in-chief and publisher Ripley Soprano, they described harm reduction as “whore and junkie magic,” and told me about the influence of 90s New York club culture on their downtown rag, plus using both art + parties to make drug education more culturally relevant… check out our convo below.

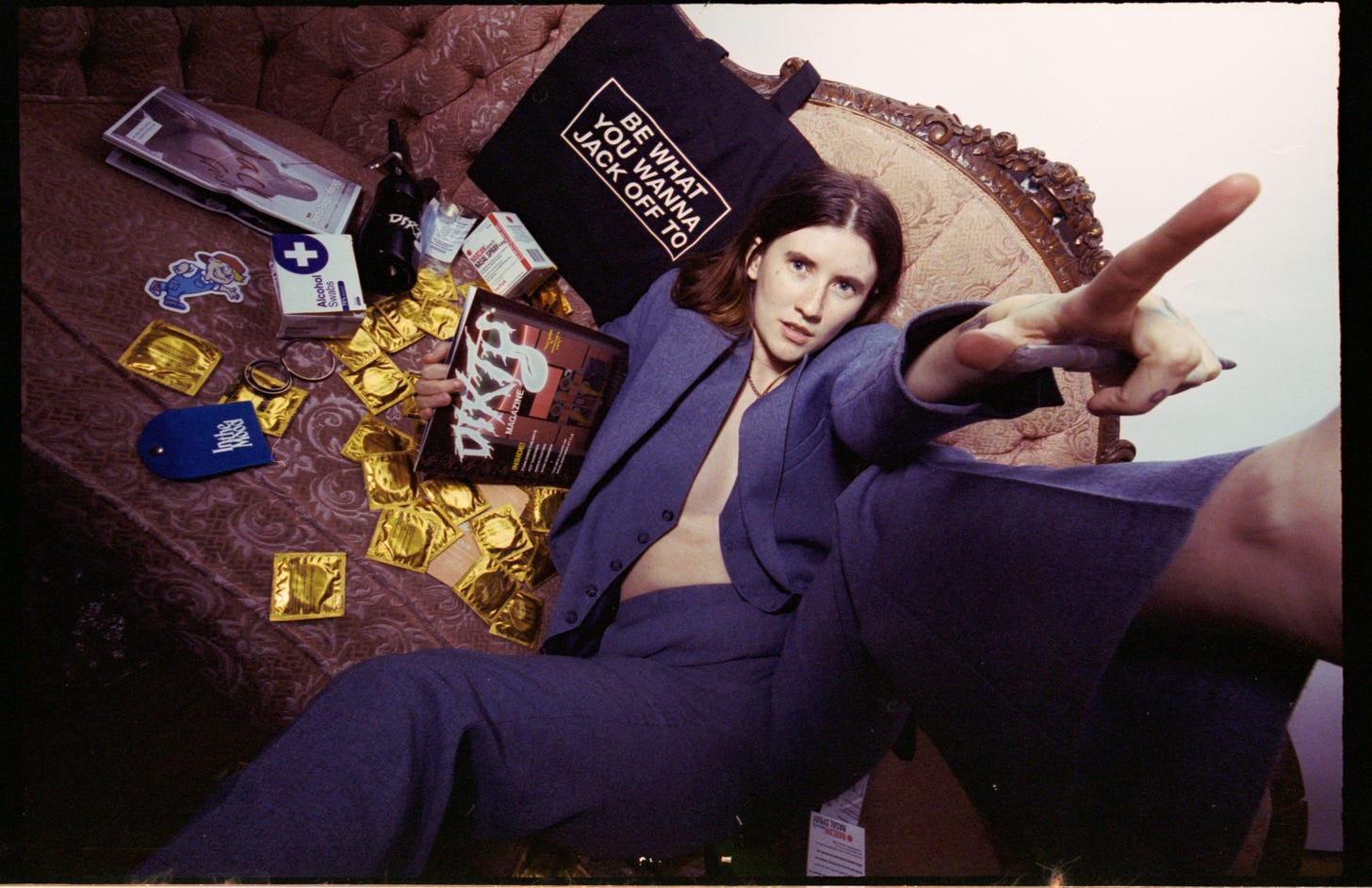

Ripley Soprano (photos by Max Lakner)

Michelle: Ripley, your magazine is sick. I’d love to hear about how you got into drugs, nightlife, and harm reduction.

Ripley Soprano: I grew up around a lot of drug users. I knew about needle exchanges just from being around people who use intravenous drugs, and when I was in college, my partner volunteered at the LES Harm Reduction Center. Then I read Pleasure Activism, which gave me insight into the history of organizing in downtown New York and San Francisco. In 2013, I worked for Mask magazine and started getting really interested in nightlife. Then in 2018, I was in a queer art fellowship program where my final exhibition was an installation of a harm reduction center in a bathroom.

I wanted to make harm reduction more attractive—less clinical, more like a dreamscape integrated into the aesthetic of my life.

I think a lot gets left out of traditional organizing, especially if you don’t make it attractive in other ways besides ‘it’s good for you.’ I had been talking to a friend about starting a new culture magazine partially inspired by Project X and other downtown rags. So Dirty started as a public health project that’s also a fashion and sex magazine.

You’re talking about Project X, Michael Alig’s magazine. I actually wrote this crazy profile on him when he first got out of jail, and have been thinking about him because he overdosed about a year ago.

Yeah, and that was around the time I was like, OK I really want to make this magazine happen because ultimately, regardless of who someone is, they just do not deserve to die in that way.

So is Dirty a harm reduction magazine?

Everyone who works on it is interested in harm reduction, but we all have different positions. Some use drugs, some are in recovery programs, others don’t use at all. So harm reduction is more like the earth that Dirty came from. If you opened the magazine, you wouldn't immediately know that, which I think is also cool.

How did you start collaborating with ASAP Foundation?

They found out about us through a shop called LAAMS on Orchard Street, which is one of the many places downtown that they have fentanyl test kits set up. We had mutual friends because I used to work with Brujas and other groups in the skating world.

Your editor’s letter in the recent issue really hit. It made me think about how harm reduction is becoming “cool” in underground culture.

The editor’s letter focused on harm reduction because of the numbers that came out recently that 100,000 people overdosed in the past year. So in the letter, I was like, ‘New York was never supposed to get clean….’ and the magazine also has essays and fashion editorials, all under the theme of public indecency. Our connection to the New York legacy is Time Square live sex shows and other stuff that has been whitewashed by the way that the city has changed.

How do you see your work building on New York’s harm reduction history?

When I think about harm reduction, I think of whore and junkie magic. It exists in some middle ground between science, community work, and public health medicine. Dirty is about broadening people’s perception of joy so they can make their own autonomous health decisions, like whether or not they want to use drugs, and just having stuff to live for. Which feels like a very downtown New York ethos, not like what exists now.

What do you think is missing in the way downtown New York is portrayed in the media right now?

There are so many more downtowns than are being described. Even within the very small depiction of Canal and Orchard Street, there is still a lot of diversity. We're just not seeing it. Like the kids that hang out on the other side of Canal Street, they call themselves Dollar Brew, and they all drink beer and skateboard.

There’s a nightlife scene. There's people who eat out every day. There's people who live on the street. There's people who live in rent controlled apartments, and their main job is to go into the Western Union every month. Most of the people who grew up downtown can't live there anymore, or they can just because of some crazy scam their family was able to pull off. So I think the main thing is just that it's not one thing at all.

Ripley + the Dirty crew

Do you see your work as a continuation of New York’s harm reduction history, or taking it in a different direction?

I think it's a bit of both. Like I wrote in the editor’s letter, there’s a reason why I'm not running a needle exchange. I realized that what I could contribute was different. Obviously, this shit has been going on for so long. What me and my friends can contribute is trying to make harm reduction cool and the only way that people really use drugs. Doing what the public health system has failed to do, which is try to address how many overdoses there have been. In terms of the legacy, also keeping it focused on the people who are most affected, which are people who use drugs and people who sell sex. A lot of projects will say, our idea is to address stigma. Our magazine isn’t for people who have those stigmas. Dirty is for people who don't need to be convinced.

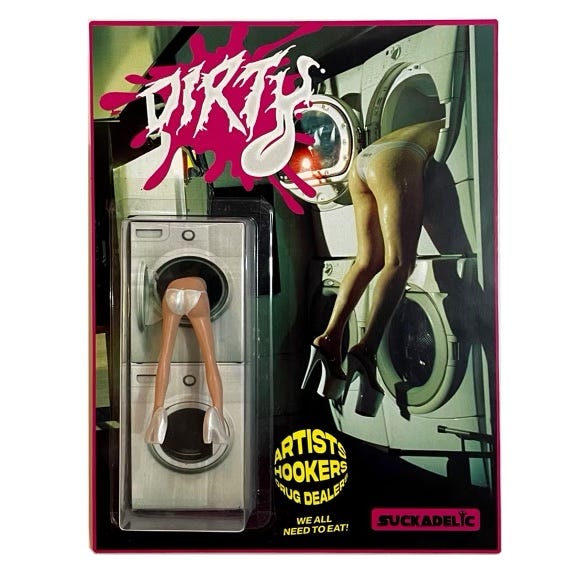

A Narcan nasal spray-inspired toy figurine that Dirty made in collaboration with Suckadelic

My impression is that nightlife harm reduction and needle exchange harm reduction have some overlap, but they also operate as different worlds. What's interesting is because fentanyl has become so ubiquitous in the drug supply, these worlds are kind of coming together.

Definitely true. There was like a sticker that me and my friend Jade who runs 69Herbs made. It said SUCK DICK CARRY NARCAN. We made that in 2018, and people didn't know what Narcan was really. Now, it seems like people have a lot more recognition of what naloxone is like and how to use it.

So you’re trying to make harm reduction more appealing to the culture through aesthetics… and like, through parties?

Yeah, I would say programming and parties. Not having these worlds be so separate and not making it as clinical. There's a reason why needle exchanges and centers are very clinical. They need to treat it like medicine in order to get access to the supplies, because it's really hard to run that kind of programming. But, we have an interesting opportunity to address harm reduction a little more like, people should be able to pursue pleasure. We have a responsibility to ourselves and each other to find joy in a multitude of ways.

That’s where the nightlife space is so potent. So do you think that harm reduction is becoming cool in the spheres you are operating in?

I don't know if it’s considered cool yet. It’s just more pervasive and recognizable… it might be in a middle area right now. It’s a genuine thing, not just people taking pictures of Narcan, which does feel different than other trend.

To finish up, could you tell me about the nightlife aesthetics that you're drawing on?

I've always been someone who's kind of in the activist world and also wanting to work for a fashion magazine. Those things felt like they had to be very separate. But what was cool about working on Dirty is that I could make something for people like me and my friends. So the references came very organically, like Project X or Big Brother, which was the skate magazine that Larry Flynt had on his roster. Also like, Nylon, which I read when I was in high school, or Cobra Snake photos, and show papers where you would find out about all the events going on.

There’s an element of trying to create something that isn’t internet or Instagram. People like Dirty because it’s in print. They want to return to the physical, like having a magazine that's an extension of the club. In that way, it's very nostalgic.