Time in a k-hole is elastic, stretching sideways into a subconscious slipstream. Only twice on the dancefloor have I sensed my timeline collapsing into preceding eras of partying, history hanging suspended as moments of shared ecstasy bounce back and forth like an echo. What a feeling: first a jolt of recognition that my rave ancestors were surrounding me, then, a flood of sentimental stupefaction.

Both times have been on ketamine.

My most recent uncanny flashback was last month in downtown Los Angeles. The rave was a fundraiser for Queer Maps—an online archive of LGBTQ bars, clubs, and other pivotal queer gathering spaces dating back to the 19th century. Each room at this party, held at the nonprofit venue Navel, was an homage to a historic queer venue, with decor ranging from a 90s-era “No Cruising” sign next to the DJ booth, to a neon-lit glory hole tucked behind plastic sheets in a dark corner.

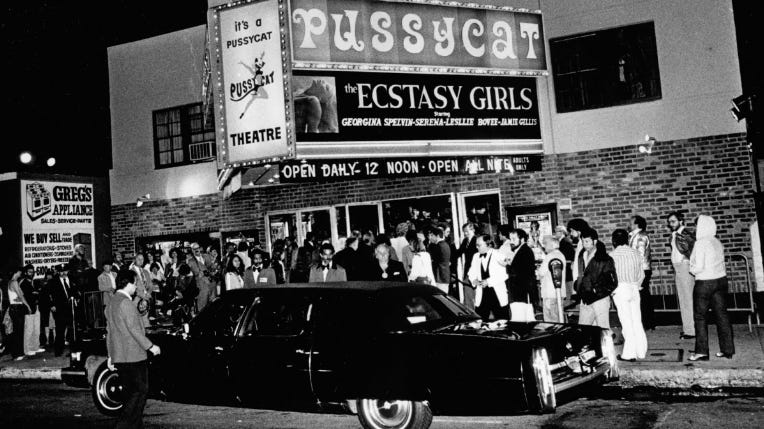

There I was, lying splat on a metallic bean bag in a chillout room dedicated to the Studs Theater. Also known as the Pussycat, Studs was an iconic porn cinema in West Hollywood that played artsy hardcore films like Deepthroat and Ecstasy Girls before going gay in the 90s. “This theater caters to men of a certain age who don’t know how to navigate through Grindr and Scruff for a sexual outlet,” said one patron, explaining how Studs was a pivotal cruising zone for a certain generation.“This is all some of these men have.”

Pussycat Theater, later rebranded as Studs, showed porn films to a wide variety of audiences (Photo via)

By the 2010s, Studs was one of the only remaining porn theaters left in Los Angeles, a dinosaur of a dying scene. Sadly, its demise is an old and familiar story: when the landlord hiked the rent last year, the beleaguered venue realized it no longer had enough clientele to sustain its operations and finally shuttered for good.

As the walls went thud thud thud to house music next door, I stretched out in the pseudo-theater and watched a montage of queer films flashing before me on a projection screen: gorilla gays in leather chaps flexing their bulbous biceps; trans legend Goddess Bunny tap dancing in a tiara; an elder Black drag queen chuckling at the camera while smoking a cigarette. Gazing at her wry smile, I suddenly felt as if an invisible cord was extending from the screen, connecting all these glorious dilettantes of nightlife, and curling down the dark well of my k-hole to finally wrap around me.

Damn! I’ve been so busy hand-wringing about the shallow simulacra of post-pandemic raving, I’d forgotten how cunty this culture can be. It took a ketamine-assisted dip into the past to remember how lucky we are, actually, to be part of this legacy. I got up and wobbled to the dancefloor, shrugging off my shirt as I joined the blob of sweaty bodies popping off like pogo sticks in a small black room. What a joy it can be to repeat history.

Queer Maps is an interactive tool that allows you to dive into a dense mosaic of queer stories buried into the streets of Los Angeles. Launched in 2019 by the DJ and nightlife activist Chris Cruse, the virtual archive catalogs over 800 spaces in the city where queer people have gathered since the 1800s. Spend enough time jumping down the websites wormholes and you’ll dust off the tales of a Victorian sex club, Mexican drag bar, lesbian autonomous zone, and even Pershing Square as an iconic cruising zone.

Queer Maps also goes beyond nightclubs and sex spots, covering other historically-significant places like the first substance abuse center and homeless shelter for queer people. Poking around the site, what also emerges is the story of how criminal enforcement of queer people has evolved over the decades.

A week after the party, I called Cruse to unpack the project—you can listen to our conversation at the top of this post. We bitched about how the structural issues choking the nightlife scene sometimes feel too entrenched to overcome; Cruse spent many years trying to lobby city authorities for change before throwing in his hat and absconding to Berlin. (This too, sadly, is an old story.)

In a sense, Queer Maps is the ultimate labor of love—a project born from hundreds of hours that Cruse and other volunteers spent trawling deep archives for any signs of the queer gathering spaces that once thrived in LA. “It’s not just nostalgia,” Cruse told me. “Let’s learn from these places. Why did they close? What made them stay open for so long?” Queer Maps remind us of what we have been—so that, maybe, we can imagine what we could be.