WHO'S AFRAID OF THE NEO-WOOK?

At Osmosis festival deep in Oregon weed country, a new strain of psychedelic raver emerges

Consider the wook: a much-reviled dance music archetype that first emerged, in a snarl of matted dreadlocks, in the parking lots of Grateful Dead shows. Dressed in drop-cotch harem pants, wire-wrapped crystal necklaces, and hooded hemp ponchos, wooks wander barefoot, trying to trade shroom chocolates for free concert tickets. When Jerry Garcia died in 1995, many wooks migrated to the dubstep scene, replacing their devotion to jangly guitars with a love for the wub. Festivals like Lightning in a Bottle, Desert Hearts, and Shambalah are now festering grounds for the contemporary wookie, and where you’re most likely to catch them six tabs deep, spinning poi to “sacred bass.”

In the 2000s, wook culture became the hairy butts of endless memes in the dance music scene. Our distaste for their feral, drug-addled lifestyles might stem from a deeper wound: wooks force us to confront the long shadow of psychedelia—its anti-capitalist spirit boiled down to opportunistic mooching, psychonaut experimentalism devolved into brain-fried stupidity, countercultural resistance cross-faded into pseudo-spirituality. These grimy drug goblins particularly plague festivals on the North American West Coast, where the underground often cannot escape the twin blades of New Age cheese and Burning Man cringe.

I was skeptical when I first heard whispers in the rave network that something interesting was happening in Oregon. The granola-ass state is the perfect petri dish for wooks to self-replicate, and has a hard time shaking off its reputation for whitewashed woo-woo. Then friends told me about Osmosis, a psychedelic music festival connected to Portland’s electronic music scene. I was curious about the West Coast network that Osmosis is both drawing from and actively building; many of their DJs come from Vancouver, Portland, Seattle, and the Bay Area—cities with vibrant but chronically under-documented rave undergrounds.

It was at Osmosis, surrounded by horses and pot farms as cybernetic basslines shook the pines, where I first heard the term: neo-wook. The phrase was circulating around the festival like an inside joke, because it so perfectly captured the subcultural flavors converging there into something familiar, yet new. “Neo-wook” forced me to contemplate questions that had never before crossed my narrow, wook-hating mind: What if the wook psyche holds a secret to resisting the logic of late-capitalism? Can wooks mutate from goofy caricature to an updated psychedelic archetype that fits this era of global club culture, post-ironic memes, and cybersigil spiritualism? Wait—am I a neo-wook too?

Osmosis happens deep in Oregon’s weed country, in an artist colony called Takilma nestled on the edge of the Sisiyou Mountains. Locals consider this region the northern tip of the Emerald Triangle, where the nation’s best cannabis has been cultivated for generations. Takilma’s original pot farmers are earthy, back-to-the-landers who fled cities like San Francisco in the 60s and 70s, in search of an Eden far from the surveillance state. These hippies were the spiritual predecessors of the wooks—staunchly anti-authoritarian, and a little rough around the edges—and the bassbin ravers of Osmosis are the latest pilgrims seeking escape from technofeudal hell.

The festival happens in late September, during the start of cannabis harvest, and we started to catch whiffs of weed’s sweet skunk as we pulled off the highway after a five hour drive from Portland, merging onto rural roads lined by bushy plants whose sugary trichomes twinkled in the setting sun. Oregon grows some of the best cannabis in the world, and the air smelled like peonies mingled with sour body odor and mulchy dirt—in other words, damn good weed. Corporations prefer to grow cannabis in warehouses under artificial lights, because total environmental control results in more valuable, higher-THC buds. Watching these plants waving in the wind like tiny Christmas trees felt like a good omen—like hippie ideals could survive on the edge of remote Oregon.

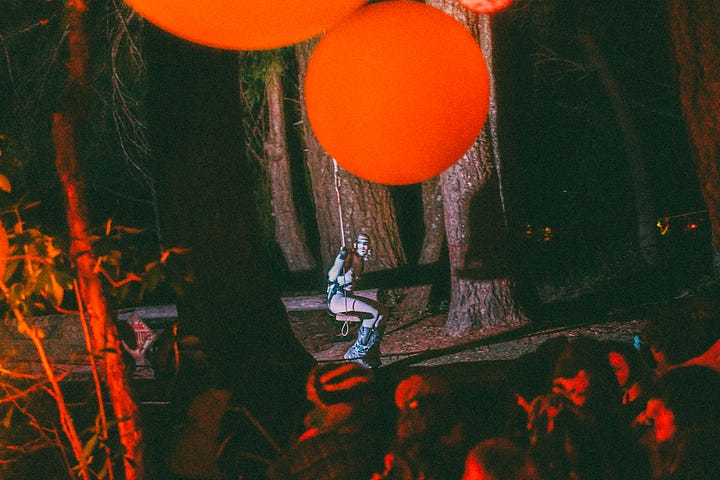

My partner and I had hitched a ride with DJs playing the festival, and the van spat us out in festival grounds. A dozen treehouses were suspended 35 to 50 feet in the air, abutting the limbs of some of the oldest oak trees in the country. During the rest of the year, these handbuilt cabins operate as a family resort and jam band concert venue called Out N About Treehouse Treesort. Some of the treehouses were connected by swinging suspension bridges; others had elaborate stained glass windows and pulley systems for luggages. It was giving full Robinson Crusoe fantasy: a DIY utopia built by an enterprising pot farmer named Michael Garnier, who spent years fighting with the authorities for the right to live off the land and in the trees.

Garnier’s resistance was an older kind, forged out of fiery clashes with the law. But behind his bureaucratic battles over building permits was a playful silliness that reminded me of the wookie psyche. On the first afternoon of the festival, I spotted him hopping off his golf cart to give light shows to slack-jawed ravers using a spinning device named “Fantasy Flakes” that he’d carved out of wood. We started chatting, and he told me about his neighbors preventing police raid on his pot farms by building a blockade out of logs and rocks. He got arrested, and showed up to court riding a unicycle while dressed as Thomas Jefferson. “Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness—that’s all I was doing!” he insisted. “Anyway,” he added, grin widening, “I won that case.”

Turns out that outlaw hippies and neo-wook ravers have one thing in common: an appreciation for a sick party. Osmosis co-founder Jake* got Garnier’s blessing to throw the festival in the treehouse resort while working as a weed trimmer in the nearby Cave Junction. (*Osmosis’ organizers requested to omit their last names; let’s just classify the crew as super chill Pacific Northwest bros who can discuss surf breaks and strains of ketamine with equal fluency.) The hippies flying from around the world to work on these pot farms reminded Jake of psytrance parties he’d been to in Europe, where he’d studied Western Esotericism. Sitting outside of a treehouse that evening as the cicadas began to sing, Jake told me that before he moved to Berlin and got into techno, psytrance parties had turned him on to festivals “as an acceleration vehicle for euphoria and transcendence.”

“You’d walk into one of the bars, and there’d be all these freaks from all over the world, speaking six languages,” he said. “It was that weird underground countercultural vibe.”

Finding liminal spaces to create tripper autonomous zones is sort of Osmosis’ thing. In 2021, Jake and his buddy Ian started Osmosis in a 100-year-old Chinese restaurant called Ming Lounge in Portland. “It was this totally trashed restaurant in the seediest part of town, and there’d be, like, people openly smoking crack at the bathroom,” said Jake, who’d been drinking there for years. “I was like, man, if you can do that in the front of the house, we can have any type of party in the back of the house.”

Festival co-founder Ian had a similar woo-woo-to-warehouse trajectory: he started DJing at yoga events, before falling in with Portland party crews like Believe You Me, Spend the Night, and Limited Edition. After acquiring a mobile Danley soundsystem, he’d often lend it to DIY parties to help level-up their sound. This raver act of service, combined with the small fortune he’s invested into the festival, led multiple guests to describe him as a “patron of the underground.”

The Osmosis crew hauled the Danley system into Ming Lounge, and began booking regulars like Succubass, gardenparty, and DJ Eft. The party’s sound, Ian told me in his deep stoner drawl, coalesced around “deep trippy techno, left-field bass, old dubstep, and weird electronic music.”

In 2023, one of Ian’s friends was offered two rooms in a giant warehouse called The Watershed to open a permanent club. The local community of architects, woodworkers, and interior designers came together to transform the run-down property into a 200-person dancefloor with a cozy bar side room. They called the club Process, and it’s played a pivotal role in Portland’s underground popping off in recent years.

That everyone-pitching-in vibe, which recalls both hippie communes and the wookie barter system, also showed up at Osmosis festival. Stages were produced in collaboration with other Portland party crews, while the boundaries between participants and staffers were often blurred. On the first night, I headed to Club Membrane, a barn transformed into a pulsing warehouse, complete with the Danley soundsystem brought over from Process. Local DJs nite bite and pip played a b2b round of ethereal techno; shortly afterward, I saw one of them working the lights at the back of the barn, and the other setting up a candlelit natural wine bar in the woods.

Inclusivity at raves can be a bit of a gamble—open the gates too wide, and you never know who might walk in. But at Osmosis, a certain cultural porousness felt refreshing, allowing for a freak alliance you might not see on more traditional dancefloors. The next evening, performance artist Kai Hynes emerged from the swimming pool like a spectral frog-god, the cold, black water licking his skin as orbs of light dangled from his slowly rotating neck. On the other side of the field, past a group of local wooks howling at the moon, was La Bohème—a caravan where Oscar Wilde-channeling bohemians and pale goths in Victorian gowns told ghost stories to guests over tea, absinthe, and rose-flavored hookah. Such a frou-frou display of dandyism felt quintessentially Portland—the hosts, Darwin and Jaden, run an underground tea lounge in the city—and somehow, the perfect counterpose to Hynes’ avant-garde butoh.

“Our scene is small, we need all hands on deck in order to make it work,” said Mauve Decade, a queer Portland-based musician who became the scene’s unofficial lore-keeper after introducing himself to me at the swimming pool, mentioning that he stans this newsletter (cute!). “Everyone has to get their hands dirty in some way,” he continued. “There’s no room or reason to exclude the Burners, the hippies, the people who might not fit in at raves in bigger cities, where the aesthetics are more coherent.”

“Neo-wook feels like the most succinct way to describe what’s happening in the Pacific Northwest underground right now,” Mauve Decade said, dropping the term into my consciousness for the first time. “There’s something about the anti-aesthetic crunchiness, the not-really-Instagrammable aspect of wook culture that really resonates here.” Neo-wook is characterized by an oscillation between cutting-edge and cringe: “It’s taking a whippet in a cold plunge, it’s a psytrance blend of “Fast Car” by Tracy Chapman at peak time, it’s the guy next to me at Liv Wutang’s dubstep set whispering light language to himself.”

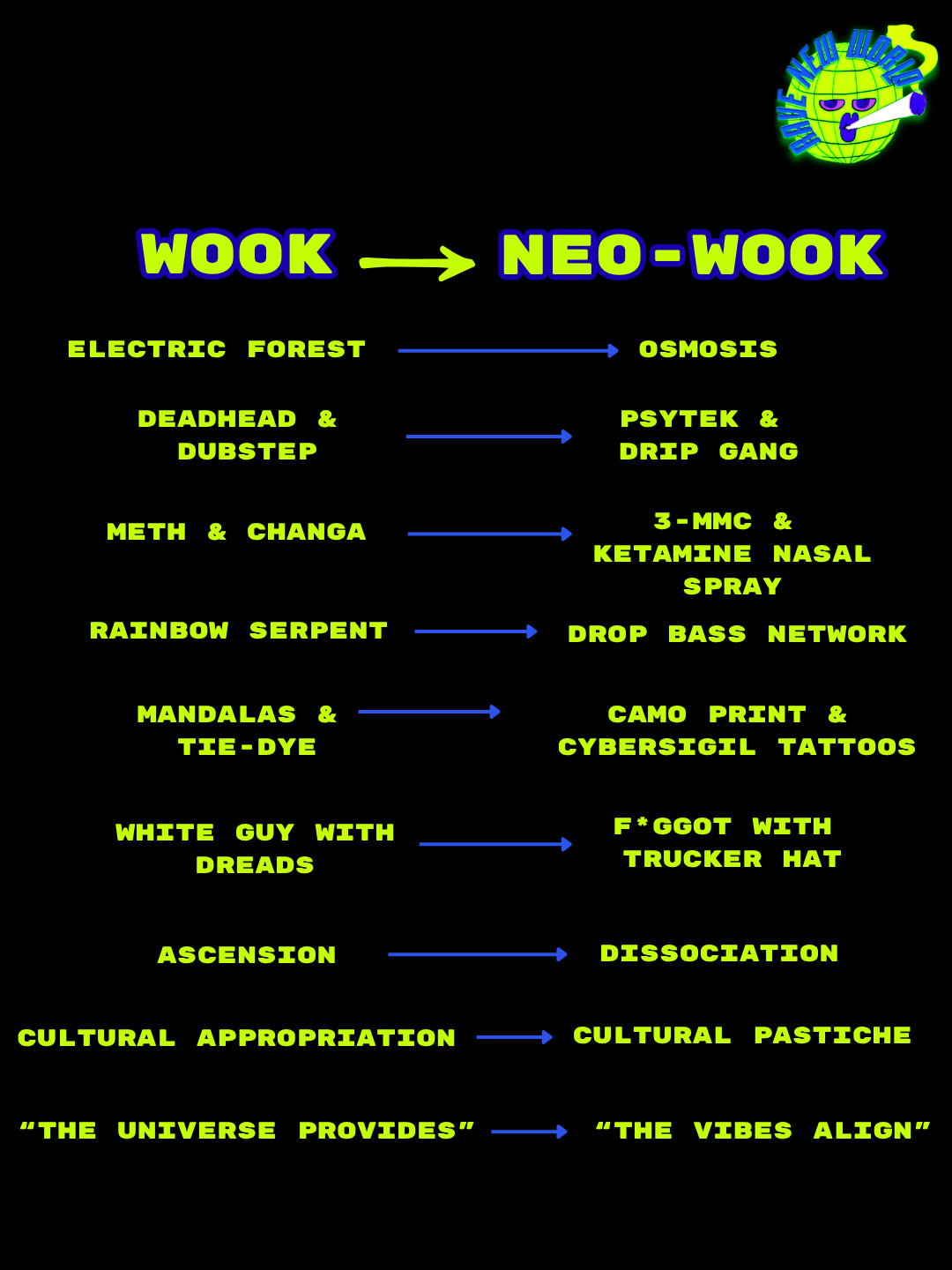

The neo-wook paradigm started to crystallize in my mind. If wooks are the brain-glazed love children of the hippie drop-out generation, neo-wooks are what happens when that archetype meets today’s post-club moment. Neo-wooks aren’t rejecting the wook completely—they’re just metabolizing “so stupid it’s genius” stoner wit through savage memes, and leaning into cringe tropes via the chaotic logic of the internet. Self-aware yet spiritually curious, the neo-wook chooses mind-melting debauchery because he knows there’s no way to truly exit the system. Yet, both the wook and neo-wook know a secret about resisting the late-capitalist logic of hyper-optimization. Fuck the microdose, they say, reveling in the ecstasy of going all the way in.

I think of the wook → neo-wook evolution like this:

Many musical performances at Osmosis felt like they were transposing wook genres into a neo-wook context: Naarm/Melbourne-based DJ Loif channeled the trippy tendrils of dusty Australian bush doofs with a psytrance-inflected set that coiled out of the speakers like smoke from a DMT vape, while Succubass reclaimed wookie bass music through her technical mastery, deconstructing the subgenre through refractions of post-club music in a frenzied whirl across three decks. Even headliner DJ Nobu dipped into a vocal-heavy 90s trance moment during his psychedelic techno wormhole, and while some of my friends sniffed that it sounded like EDM, I was hooked.

Tripping through Osmosis felt like witnessing overlapping, evolutionary stages of counterculture—the hippie commune, the DIY warehouse, the queer art salon—converging in a forest that smelled like pot. Part of what held it all together was the festival’s strong visual identity, overseen by DJ Eft, whose flyers, signage, and merch drew from organic, amoeba-like forms and 90s rave posters. When I asked about his aesthetic inspirations, he replied, “Honestly, a lot of it is channeling my inner plant sage, psychedelic organic guidance, and connection to the earth.”

On the festival’s final night, I found myself snuggling with my new friends at Osmosis’ ambient stage, The Mizaji Lounge, contemplating the softer side of the neo-wook. Tucked in a forest clearing under the star-streaked sky, the resin lamp-lit den felt quasi-sacred—as if the fecund soil had sprouted an enchanted hideout where the soul could drift. Surrounding me were contingents of radical queer elfs, ketamine party kweens, post-Berlin psychonauts, and enlightened stoner bros, while above me, dozens more bodies swayed in a massive hammock strung in the trees. A four-point Mobius rig enveloped the enclosure in warm vibrations like a womb. Ambient performances at parties are usually side-shows, relegated as chillout zones for ravers with dancefloor ennui or bad knees. But The Mizaji Lounge felt like a new frontier in psychedelic music: less “transformational” festival, and more experimental listening den

“Ambient” here was an umbrella term, ranging from a live hardware set by Othrwrld that washed over like a healing sound bath, to the post-internet surrealism of VVX Subhunters, who invoked the spirits of techgnosis through digital glitch. The audience’s willingness to engage in the psychedelic practice of deep listening was on a level unlike anything I’ve experienced at a festival, with the crowd sitting cross-legged in rapt attention, whistling gleefully at the weird music their friends were playing.

No one embodied the spirit of the neo-wook more than Ben Bondy and Special Guest DJ, who pulled up in trucker hats, chain-vaping. Ben’s set, a romp through sultry R&B and sad boy SoundCloud rap, revealed the tender heart of the based god. Special Guest DJ offered an avant-garde pastiche of Americana, switching from country tunes to intimate voice notes to Jimi Hendrix’s “Star Spangled Banner” like flicking through the dials on rural radio. This ambitious set could have flopped in less knowing hands, but here, recontextualized through the intimate setting and filtered through the DJ’s genuine glee, it approached something close to profundity.

As the festival drew to a close, I realized that the mutation of the neo-wook could only happen at Osmosis in Oregon, where outlaw libertarianism fuses with West Coast hippiedom. The state was the first to legalize psilocybin therapy, and its psychedelic culture still carries the spirit of the back-to-the-land movement, recast for the age of ketamine. The festival also thrives off a countercultural communal ethos, while its dancefloors pull psychedelic substrains through dance music’s evolution from West Coast bass to Berlin techno to post-internet hyperpop.

On the final morning of Osmosis, as people packed up their camping sites, news broke that Trump was sending in the National Guard into Portland, saying that the “war ravaged” state was “under siege from attack by Antifa and other domestic terrorists.” It was a reminder of what the neo-wook, laughing in the ruins, has always known: utopias are fleeting and impossible to maintain. As I boarded the van back to the airport, I thought of something Jake had said:

“ We live in a very disenchanted world, out there in capitalism and scientific consensus material reality. But you can create a temporary autonomous zone where people can forget that we’re constrained by all these external forces, and have a moment outside of it all. That’s a really potent vat for these rich experiences—whether they’re relational, communal, ecstatic, or psychedelic. A good rave is like a spell.”

NOUVEAU WOOK-WASHED

While I respect LHOOQ’s position on the so-called “Neo-Wook” archetype—and welcomed the brief intellectual detour of an article attempting to deconstruct the idiosyncratic gathering I hold dearest to my heart—I’d like to offer a counter-argument, or at least an addendum, to this discourse surrounding the “psychedelic-festival” known as Osmosis in the Trees.

This grassroots event, still in its fragile infancy, began a mere three years ago as a modest, rickety experiment—its raw seams perpetually exposed. (Charming at times, infuriating at others.) Yet its backbone was clearly built not of fabric but of tenacity.

Fast-forward to now—TL;DR—those close to the creators have witnessed a transformation so profound it would leave Dario Amodei sweaty-palmed and weeping into his MacBook. Civilization VII: gone to the scavengers. The large language model: reduced to a beanbag chair. Want to make wine? You might get grapes by year three—if nature cooperates. Some (very lucky) children still breastfeed at three. My favorite alpine cheese takes 3 years to reach perfection.

And what we all witnessed this third legendary year in Takilma was precisely that: a testament to determination, to grit. A herculean feat of maturation, born of a seed planted with love and nurtured by Danleys. (Life is good.)

Allow me to hypothesize: Why does the volunteer tomato that shoots up in your compost pile always yield the sweetest fruit? Why do words spoken after intentional silence vibrate with such unexpected depth? Osmosis in the Trees (OITT, for the acronymically inclined) is no different. It manifests our generation’s longing to plug into nature while refusing to renounce the technomagic that haunts our synapses.

It’s the anti–invite-only “festival in the woods” curated by insufferable New Yorkers nostalgic for the golden days of Nowadays—gagging as they scrape mud from the toe-slits of their Tabi boots. OITT is the energetic sacrifice of an aesthetic family; a ritual nod to free-tek legends and tree-sitters; a Deleuzian Morse code slicing rib-eye steaks into roses.

The Osmosis NRG is fueled by an optimism so precocious I’m shocked it hasn’t yet been minted on pump.fun. And lest ye scoff at this coastal behavioral anomaly—breathe deeply, this might be your last.

Still breathing? Good. Try identifying the species of conifer currently seducing your olfactory cortex (Douglas fir). Now imagine yourself being whisked away from frenetically ambivalent lasers by Nathan’s hoverboard, landing squarely in Izzy’s 3 a.m. broth station at the town square. This is not a “performative” festival—it’s a time-based performance.

Each actor is their own NPC; friends and foes alike become Diane Arbuses of the rave world, refusing the hypervigilance of those obsessed with projecting the aura of “better-than-thou” or “if I were curating…” Instead, they bend like prairie grass in the wind, surrendering to whatever direction nature—algorithmic or otherwise—deems fit.

“Neo-Wook”? Please. Wook-Nouveau feels far more apt. This is the zeitgeist of the Pacific Spirit: a burgeoning raincloud of self-sufficiency and mutual aid between hedonistic homesteaders and techno-anarchists. The Nouveau-Wook exists with intention. This Darwinian sacrament imbues them with a magnetism perceptible only to fellow psychedelic pragmatists.

The Nouveau-Wook revels flagrantly in the cognitive dissonance between deep listening and maximalist consumption—an ecstatic Fibonacci of absurd pleasure. Their bloodlines bubble with ancestral trauma: tens of thousands of dollars down the drain for the cheap thrills of smart-car-sized nitrous balloons and imperial IPAs girthier than a Big Gulp (“DAD, are you OKAY?”) at the fifth Phish concert of the week—or, conversely, the existential ennui of the Midwestern mansion, void of any intentionality beyond square footage and Yankee Candle stench. (Many of us, tragically, can claim both, and the PTSD to match, blooming merrily in the Petri dish of our millennial childhoods.)

The Nouveau-Wook sees beauty—and humor—in all. She eats spaghetti from a plastic Container Store drawer, sips a diet energy drink at the renegade natural wine bar pop-up in the mystic woods, and whispers 2 + 2 = 5 as her mantra of spiritual collateral. She knows there’s nothing to gain from the techno-capitalist zero-sum game we labeled as reality.

She is a stick-and-poke Bitcoin symbol. A tear dropped onto the last bump of ?. Poison ivy tucked between her Tabis, used to surreptitiously tickle her ex’s neck on the dance floor as he K-holes.

Osmosis in the Trees is equal parts genius and chaos: planning meets improvisation, a puckish electricity dissolving boundaries between humans, genres, and even time. The critical theory of Osmosis is action—it is creation, it is movement. It is ecstasy, pure and unmarketable, unhindered by language or expectation. It’s a glass of cold spring water soaking through your hoodie because you forgot the cup. It’s the dreadlock that formed at Club Membrane. The embroidered hoodie you still haven’t taken off, now glazed in a palimpsest of oil and sap stains.

It’s Dieter Roth’s rotting art catching a stranger’s piss falling from Duchamp’s fountain—a neurodivergent rainbow of talent gathered among the endangered lilies of the Kalmiopsis wilderness, all surrendering to corporeal pleasures.

The Nouveau-Wook is both object and symbol: the return of la vie bohème. And it is in the trees, under the net, surrounded by friends, that she will once again caress Nirvana. Nevermind.

You're losing your New York edge, Michelle. And all I can say is "congratulations." LOL