THE MUSEUMIFICATION OF TECHNO

Can rave culture, in all its messy contradictions, be enshrined by elite cultural institutions? Reflections on Carl Craig's "Party/Afterparty" exhibition

“Art is the luxury asset that moves in when the party’s over.” — New York Times review of ‘Carl Craig: Party/Afterparty,’ August 2020

In Los Angeles, you can measure a show’s hype by the number of filthy bus stop benches it’s advertised on. For the last few months, bright yellow signs publicizing CARL CRAIG: PARTY / AFTERPARTY at the MOCA Geffen museum have been plastered across the city’s public transit stations, sandwiched in between Hollywood movie posters and public health campaigns about STDs. These ads, which resembled rave flyers, struck me with their hyper-visibility. Sure, there are party fliers and music festival posters all over these streets too, but never so ubiquitous and reeking of institutional money. Lauded by the media as the one of the first major art exhibitions by a techno artist in the United States, Party/Afterparty is a groundbreaking show—and the museumification of techno* brings up both potent and challenging questions.

*the “museumification of techno” is a phrase I grabbed from my friend Emily Witt, thanks sis!

Party/Afterparty, which concluded last weekend with a sold-out dance party, is the work of Carl Craig, a 53-year-old DJ/producer who was part of Detroit techno’s second-wave in the early 90s, and has built himself an extremely successful career as one of the industry’s most ambitious stars. Always expanding the boundaries of techno, Craig has collaborated with classical pianist Francesco Tristano and a Paris-based orchestra on 2017 album Versus, as well as dub techno producer Moritz von Oswald on a release based on Ravel and Mussorgsky. Now in his rave elder years, Craig has settled comfortably into the role of an internationally-touring celebrity DJ/Fedora Guy, and some of his DJ mixes, like the one for Ministry of Sound’s Masterpiece series, have slid into mediocrity according to critics. Yet, as Party/Afterparty demonstrates, his zeal for elevating techno into elite cultural spaces remains strong.

As one of Detroit’s elder statesmen, Craig is widely worshiped as an OG legend, musical pioneer, and powerful business magnate at the top of his game. When I took a tour of Detroit with him in 2016, he described himself as near the top of the city’s food chain, and the hero’s welcome he received by all the DJs we encountered that day suggested that he might not be wrong. When Party/Afterparty debuted during the pandemic in 2020 at Dia Beacon in New York, it immediately became a critical darling. The show was widely praised for highlighting the Black roots of electronic music—a recognition many see as long overdue—and the New York Times raved that “Dia, with stunning confidence, establishes that Black electronic music belongs in the lineage of American and European art and industry.”

Many critics also noted that the show’s poignancy drew from the ambient sense of loneliness, alienation, and yearning for dancefloor communion during the lockdowns. Deprived of actual parties that summer, many friends from the New York rave scene took the Amtrak upstate to Beacon to view the show. Some told me they wept as they danced in the nearly empty, social-distanced room. It was the closest they’d come to raving in a long time, and the strobing lights and perfectly-tuned soundtrack formed a spectral reminder of the ritual that had defined their lives.

If Party/Afterparty derived much of its efficacy from the lockdown’s social deprivation, its rerun three years later at the MOCA Geffen must be understood within today’s shifting cultural contexts. Since the lifting of lockdown restrictions, raving has exploded into the mainstream, largely driven by Gen Z baby-ravers who came of age during the pandemic. An inter-generational, intensifying yearning for escapist reprieve in the face of climate collapse and late-capitalism’s tightening chokehold has also boosted raving’s hedonic appeal. Reflecting these subliminal desires, 90s rave aesthetics have flooded fashion runways, Pinterest trend reports, and creative mood boards for glossy music videos shoots.

Correspondingly, any lingering notions of rave culture’s alterity have begun to be eclipsed by its trendiness amongst tech-billionaires and professional elites. It’s hard to cling to claims of subversiveness when Elon Musk is trying to get into Berghain, the Goldman Sachs CEO is a DJ, and even your boss’ boss can be spotted at Nowadays, singing along to the Yaeji track they just discovered on Spotify.

When Party/Afterparty opened at MOCA in April, the star-studded MOCA gala featured a clubbing theme. Craig showed up in a Burberry look to DJ alongside his buddy Moodyman to a crowd of billionaire benefactors, famous artists, and Hollywood actors, including, uh, unwitting rave fashion icon Keanu Reeves. The event spoke to rave culture’s increasingly cozy proximity to the fashion and art worlds. How long until the next Met Gala theme is “techno”?

Another pertinent new context surrounding this edition of the exhibition is Craig’s recent decision to publicly dismiss and belittle women who accused Derrick May of sexual assault and attempted rape. May, who Craig considers a close friend and mentor, was a member of the Belleville Three—a trio of Detroit DJs credited with inventing techno in the early 90s. Following the publication of two bombshell articles by journalist Annabel Ross in 2020 and 2021, Craig stood up for May on Twitter, changing his bio to read: “I DON’T TURN MY BACK ON MY BROTHERS. TECHNO4LIFE.” He also used his industry clout to ban Ross from reviewing Movement, a techno festival in Detroit, then took his bullying to social media by sharing a mean-spirited image of Ross created by fellow DJ Omar S, with May’s face photoshopped over her friend.

“It’s not surprising that Craig and [Omar S] would want to support May, a trailblazing Black musical icon whose success paved the way for their own,” wrote Ross in a Medium post. “But to do it so publicly and mockingly is a slap in the face to survivors of abuse everywhere. It’s a damning display of toxic male solidarity in a scene where women, trans and non-binary people are used to coming last.”

Craig’s trivializing and juvenile reactions to these serious allegations of abuse contrasted with his work as a trailblazing leader in the community, and these conflicting factors made it difficult to know how to feel about the exhibition, my ambivalence further compounded by the suspicion that whatever makes rave culture feel so alive cannot be contained, in the first place, within the rarified walls of elite institutions.

So the other day, when I drove by another filthy bus stop bench and saw that the exhibition was ending later that week, I decided to fuck around and find out for myself what’s really going on.

“When someone walks into a gallery and there’s a party going on, that can be really cool for people—but it could be a bit Disney.” — Carl Craig, BOMB

The MOCA Geffen is located in a 40,000-square-foot warehouse that was used by the city as a police car storage unit before it was remodeled by Frank Gehry into a contemporary art museum. This backstory echoes raving’s temporary and autonomous transmogrification of post-industrial spaces into ephemeral utopias—except, of course, guerilla ravers never worked with celebrity architects, which is why the parallel here is ironic.

In fact, according to Craig, Party/Afterparty landed at MOCA Geffen after its initial run at Dia Beacon because it looks so much like a rave cave—a design feature that museums in, say, London or Berlin, may have lacked, even if those cities are better known for their rave scenes. (Of course, LA also has a vibrant rave history too, but structural roadblocks have pushed the splintered scene far underground—an issue we explored recently with nightlife activist Chris Cruse.)

In an interview published in a brochure at MOCA, Craig noted that this sense of spatial dislocation—of being outside the usual nightlife hubs—was essential to the exhibition. “It was more poetic to do it at Beacon because it gave the opportunity for people to come from Manhattan to experience the piece in a setting that is [calmer],” he said. “There are clubs like Sound and there are warehouse parties [in LA,] but it doesn’t feel so established as in New York. So I feel doing it in LA is gonna be as poetic as in Beacon.”

When I arrived on a Saturday afternoon in July, the museum was sparse and attendance slow. The outdoor patio, scorching under the bleach-white sun, was vacant except for a couple DJs from KCHUNG Radio, spinning a set of lush jazz from a red shipping container-studio that is permanently set up outside the museum. A sculpture of gnarled airplane parts by Nancy Rubins towered over the entrance. Both the DJs and the twisted stainless steel seemed like fitting preludes for the exhibition.

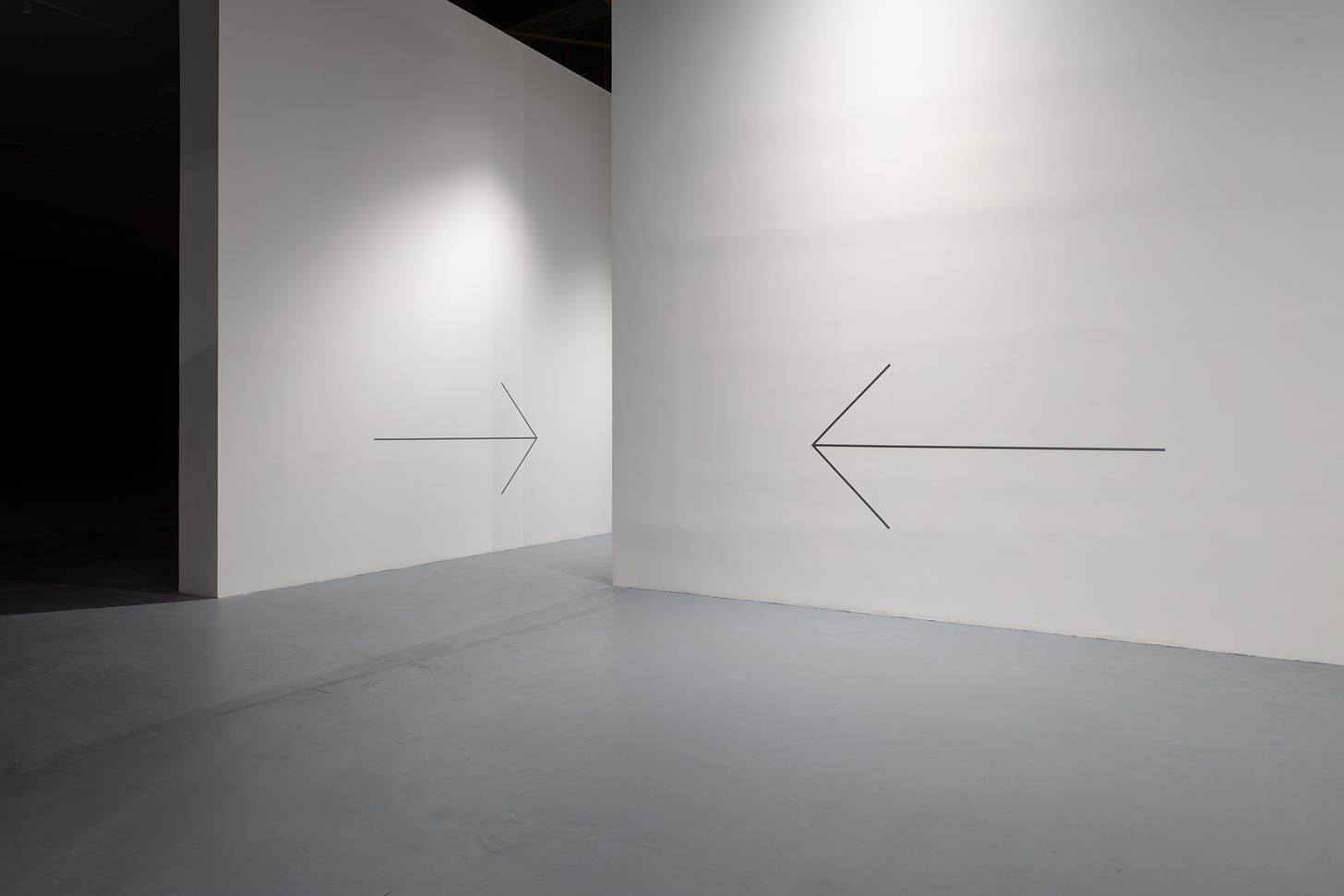

On MOCA’s website, Party/Afterparty is described as an “immersive environment” (aren’t they all, these days?) that “evokes the collective ecstasy and desolation found only on a club dance floor.” The continuously looping exhibition soundtrack and light show is designed to follow the arc of a typical club night—from anticipatory beginning, to climax, to melancholy comedown—from the perspective of Craig. As I entered the lobby and walked past the front desk, the muffled oontz oontz oontz of a kick drum grew louder as I turned each corner, stomach fluttering with reflexive anticipation at the familiar stimuli. Two glass doors finally opened into a darkened room, where the silhouettes of other visitors danced awkwardly behind a plexiglass screen.

Sounds seemed to emanate from every part of the room, thanks to a meticulous set-up of four-point speakers on the ceiling that added extra layers of audio to the music emanating from speaker-stacks in each corner of the vast room. The soundtrack of Party/Afterparty runs in a 30-minute loop, with the first half sprinkling familiar rave sonics—Hoover synths, Doppler effects, low-pass filters—over a minimalist palette of dub techno. The melancholic mood gradually climaxed into moments of catharsis, when the ceiling skylights would flap open flooding the room with sunlight—a simple yet surprisingly effective way to conjure the feeling of a truly cracking rave at sunrise. Craig has said that this effect was a reference to Panorama Bar, where one of the venue’s signature moves is to flap the shutters during particularly impressive moments of a DJ set, like a round of applause from the house.

In the “Afterparty” segment, the techno fades away and is replaced by a ringing sound that mimicked Craig’s tinnitus, followed by a garbled voice saying barely discernible words—something about “music” and “synthesizers”—over a wall of static and feedback noise. This section was perhaps the most affecting, serving as a meditation on the consequences of raving as a flipside to its pleasures.

“It’s interesting to experience the rave, within the evisceration of the rave,” said my partner, as we danced together, then separated, losing each other as we made our own ways around the room. Without the usual crowds, smells, and overwhelming stimuli of a typical dancefloor, the room was an exercise in minimalist rave aesthetics stripped of everything except for sound and light.

Yet somehow, as I gazed up at the afternoon sky, a dull ache rippled from my chest. The absence of people, and the prevalence of silence within the composition, created a spectral hauntology that was surprisingly affecting. I was not expecting to feel anything in this rave simulation, but it was these ghostly, lonely moments in the quiet spaces in between crescendos of strobing intensity that gripped me.

As I lurked around the exhibition’s periphery, I noticed that most visitors congregated in the middle of the room, where a giant X on the ground marked what Carl has described as a sonic “sweet spot”—the place where the music sounds fullest. Occasionally, the X would be illuminated by a golden spotlight, which would flash on for a few seconds before fading back to black. “I want people to have the possibility to connect with their spirit,” Craig explained. “To have that spiritual experience, to walk to the center when the light comes on.” Fittingly, a man walked up to the spotlight and outstretched his hands into a Jesus position—reminding me of the pose that famous DJs love to assume in the booth as they play to adoring crowds.

Regardless of Craig’s intentions, it turned out that the X marked the photo-op position for the exhibition, with most people whipping out their cameras to capture their friends posing under the spotlight. I am certainly not immune to the impulse—the seduction—of performing for the ‘gram. But the wall of glaring phone cameras and atmosphere of self-conscious theatricality in this zone reminded me of why I hate cameras at the rave: because unless they are wielded with discretion and artistry, they almost always ruin the vibe. The true spirit of raving is allowing for individuality to dissipate into a collective whole, but this spotlight seemed to embody the dispiriting direction the culture seems to be moving towards: the performance of pleasure for social media content.

The spotlight, as my partner pointed out, also holds a special significance in Los Angeles—the seat of Hollywood and celebrity culture. Seen in this context, the exhibition’s perfectly positioned lighting system, alternating between cinematic shadows and radiant glows, gave it an air of slick cinematography, as if we were standing on the set of a rave-themed music video. The pervading feeling that we were meant to photograph, and be photographed, is ultimately what drove home that we were in the dead space of a museum—a place where culture is preserved for the public to gawk at, rather than actively created. Only when the lights went dark did this awkward performativity fully dissipate, and there was a sense of being able to breathe—to just be.

On the other hand, the museum can also be appreciated as the most publicly-accessible gateway to rave culture, as exemplified by the diversity of people who visited the exhibition that day. Two toddlers danced giddily to dub techno, without any preconceived notions of the stigma this scene still holds, wobbling around me as I walked towards the exit, back into the scorching afternoon.

A few days after I first visited the exhibition, I returned for the closing party—the third of a series of “raves” that took place after-hours at the museum, in collaboration with Secret Project Robot and Insomniac, two of the biggest EDM promoters in California. This final session featured Moodymann, DJ Minx, and Erno; tickets sold out almost as soon as the event was announced.

There was a literal day-and-night difference in the museum’s atmosphere compared to my last visit. The outdoor patio was brimming with guests, ranging from well-dressed museum curators to wild-eyed EDM party girls, art world culture vultures, and nightlife scene queens, all schmoozing or wandering around the space as if in a daze. In a black-box-shaped room next to the Craig exhibition, DJ Minx presided over the dancefloor, delivering thundering big-room techno amidst strobing columns of light at the ungodly early hour of 9pm.

My dinner still hardly digested, this hard techno atmosphere was wayyy too overwhelming, so I retreated into the exhibition, which had become almost like the party’s default “ambient” room. This time, the energy in the room felt distinctly deflated—Craig’s minimalist subtlety eclipsed by the audio-visual assault next door. Partygoers milled around as if waiting for something to happen, or posed self-consciously for photos in the X spot. How funny that an exhibition of abstracted rave aesthetics doesn’t work when there’s an actual party happening at the same time.

The party also felt sterile within the museum’s sanctioned confines, overcrowded and over-policed like a concert, complete with a penned-in drinking area for those over 21, and security that kept popping out of the crowd to tell people to put out their joints. The dancefloor finally caught a vibe in the last 45 minutes of the party, when the crowd thinned out to mostly club kid queerdos, and Moodymann pulled a choreographed dance behind the decks with two women donning his T-shirts, shouting on the mic: “Don’t ever let anyone tell you WHO THE FUCK you are!” as the crowd burst out in cheers.

Walking out of the party, I thought about how a museum can be a fitting place for an educational rave simulation—but raving’s anarchic freedom, sweaty licentiousness, and un-surveilled freedom are antithetical to the codifying authority of the museum. The messiness of rave culture also extends to the ugly realities lurking behind its seductive sheen of hedonic pleasure—namely, how drugs, power, and money often cover up how some of our heroes might be monsters. Craig, who has devoted so much of his career to uplifting Detroit techno, might be especially reluctant to sully the reputation of his friend May, who has been written into the textbooks as one of the creators of this sound.

The museumification of techno is rightly cementing its Black pioneers as canonical figures. But who gets to be chosen as the ambassadors of this culture, and who gets erased, or dismissed, as inconsequential to the grand arc of history? Can we preserve and perpetuate the important narrative that techno is Black, while also acknowledging that toxic masculinity and sexual assault are entrenched in both techno’s past and contemporary scenes? Or are we too afraid that piercing its romanticized mythology may derail the upward trajectory of this culture—just at the moment when it’s finally getting its due?

“Preserving cultural myths, and being able to book DJs who make other people money is seen as a lot more important than whoever they might have abused, and the consequences of that,” said Ross, when I called to ask her what she thought. She might be right. But until we address the rot at the core of this industry, the paradise we’re painting for the gaze of the wider public is nothing but a simulation.

"The true spirit of raving is allowing for individuality to dissipate into a collective whole" -- Well said!

Only when you described the shutters did I realize I actually saw this piece at Dia:Beacon, but experienced it nearly exclusively as architectural art (which I loved). The X made no sense to me but did remind me of an IMAX theater my friend worked at, who showed me the magic seat all the speakers were calibrated to.

I am a small museum guy late to and outside-looking-in on rave and dance culture, but I am curious if you’ve been to the Underground Resistance studio and DIY museum in Detroit. You basically have to knock and get lucky or text the guys behind it, but I think it (along with a whole collection of modern wunderkammers dotted across roadside America) shows how true self-curated vernacular “museumification” can work.