HOMELESS PEOPLE ARE THE UNDERDOGS OF THE BLACK LIVES MATTER MOVEMENT

At Philadelphia's housing autonomous zones, they're finally taking a stand

A child plays in the Philly autonomous zone (photo by me, with permission of mother)

Strange whispers about an autonomous protest zone in Philadelphia floated my way in June, back when I was still at the CHOP in Seattle, where my summer of protest reporting began. “I heard it’s really gnarly, like lots of stabbings and tweakers,” said a friend who knew someone on the ground. Unlike the occupied protests in Seattle and New York, the Philly protest zone is explicitly a homeless encampment. Inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement, the sprawling tent city located in one of Philly’s most bougie neighborhoods has positioned itself as a protest against police violence, housing inequality, and government corruption; this strategy has been remarkably effective in staving off city sweeps. From Seattle to New York, Portland to DC, every occupied protest that’s sprung up in the wake of the Floyd uprising has been quickly shut down by cops. Which makes this nearly three-month-old encampment in Philly the last autonomous zone standing.

The Philly zone is shrouded in mystery, and many people in the other autonomous zones I’ve visited didn’t even know it existed. Scant news reports, mostly from local outlets, are centered around the city’s ongoing negotiations to clear the space, which were stymied in mid-July, when the CDC recommended that houseless people should remain in outdoor encampments (instead of indoor shelters) to prevent the spread of COVID. Philadelphia’s mayor announced that he would be personally stepping into the talks with the autonomous zone’s activists leaders—a coalition comprised from the Workers Revolutionary Collective, the Black and Brown Workers Co-op, and Occupy Philadelphia Housing Authority (Occupy PHA). Yet, at least from afar, it didn’t seem like those talks were going anywhere.

I wanted to understand how houselessness intersects with the Black Lives Matter movement—and why it’s become an integral issue for every autonomous zone I’ve visited. Houselessness is often regarded by the powers-that-be as an apolitical afterthought: when the NYPD dismantled New York’s Occupy City Hall last month in a surprise early-morning raid, Mayor De Blasio dismissively said the occupation “was less about protest, and more of an area where homeless folks were gathering.” But housing has always been a key driver of racial inequality, and the role of police to preserve the sanctity of private property over human life has become gruesomely glaring in this wave of political unrest. What does it mean when everyone flocking to a no-cop zone in search of safety and shelter are houseless people of color?

Kids playing on a swing made from a skateboard at the encampment

So earlier this week, I strapped on my backpack and headed into the zone. There are two autonomous zones in Philly now—the original one on Ben Franklin Parkway, and a smaller encampment that sprung up in early July opposite the Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA) headquarters. I decided to check out the smaller one first. “You’re gonna find a lot of Burners and gutter punks,” said a DJ friend, who dropped me off on her way to get botox. I hopped out and started snapping pics of the barricades, which lined the perimeter of a leafy field where several dozen tents were set up. A few feet away was the PHA headquarters—a spanking new, $45 million dollar building that glimmered in the searing afternoon heat. “Hey!! No photos!!” yelled a guy sitting inside. A white woman with piercing blue eyes and a Muslim headscarf approached me. “Ya’ll have to understand that working with the media is how we win,” she told the man, welcoming me into the zone.

Jennifer Bennetch, activist leader of Occupy PHA

Jennifer Bennetch, the co-founder of Occupy PHA, is an integral leader of the Philly housing protest’s vanguard. As her two young children played around her feet, she explained that she was formerly houseless, and had learned the tangled intricacies of the city’s housing system through first-hand experience. “The PHA is a cash cow for the city,” she told me, explaining how the field we were standing in was the meeting headquarters for a Black-run motorcycle club, before the city cleared them out and announced plans to build luxury condos. “This used to be a community,” she said, “Now it’s just a bare wasteland.”

The PHA building is surrounded by signs of its plans to build luxury condos

Jennifer had been showing up to weekly board meetings since 2017, and took paralegal classes at a community college so she could learn the legal lingo. “At the meetings, I started to see how PHA was intentionally blighting the neighborhood, then using that blight to seize land from private owners and sell off that shit to private developers—basically using their governmental power and money to rapidly gentrify long-term residents out of the neighborhood,” she explained.

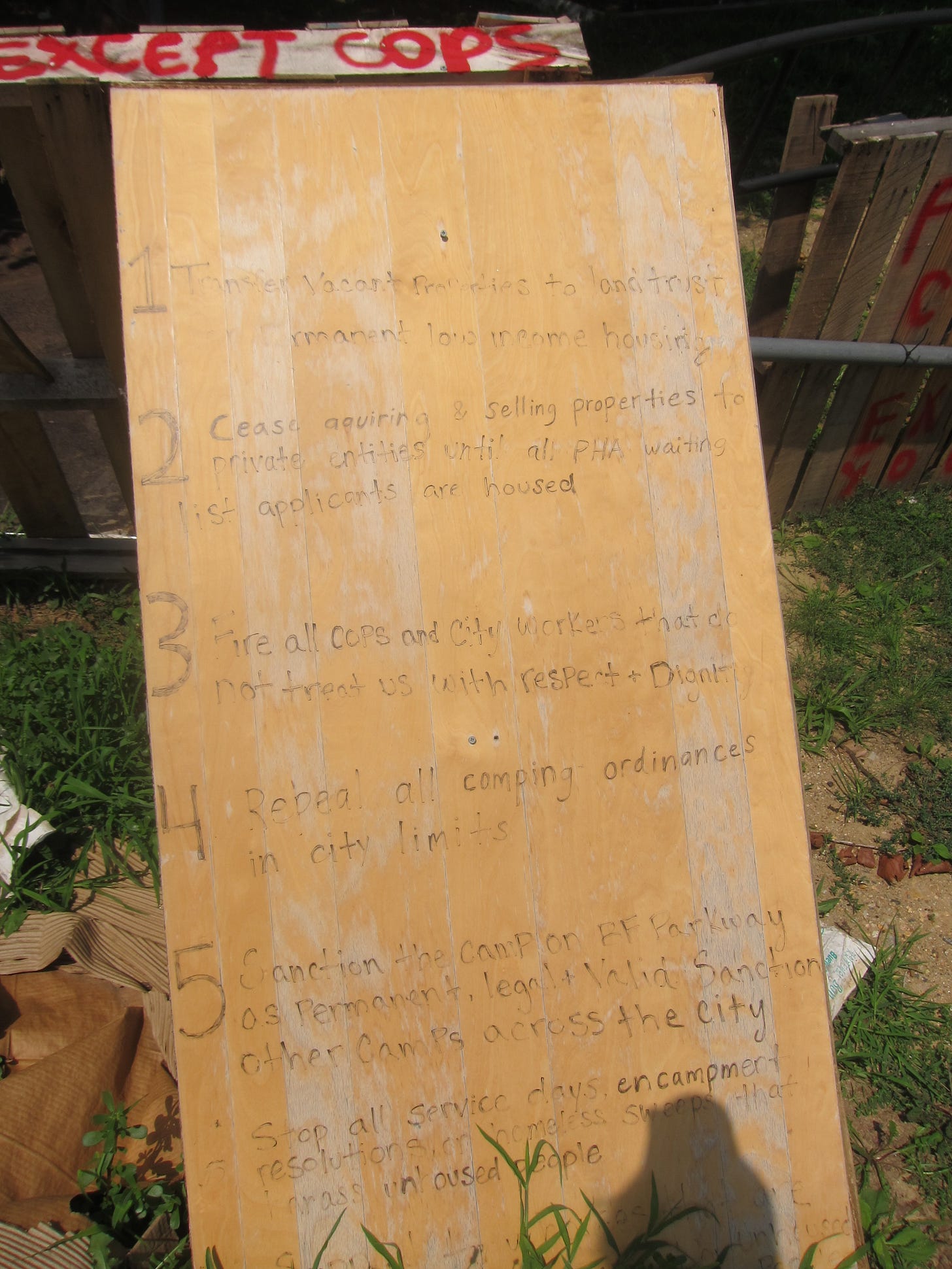

The Philly encampment’s sun-beaten board of demands

In Philadelphia, the poorest major city in America, 1 in 4 families live below the poverty line. On any night, nearly 6,000 people are homeless, and PHA’s waiting list for affordable housing is 50,000-people deep, with an average wait time of 13 years. Meanwhile, PHA’s annual budget is roughly $400 million, and its CEO makes almost $300,000 a year, more than the mayor of Philly. Thousands of PHA properties are sitting empty despite the clear need for this housing—so Jennifer and other activists have been busting into these vacant houses, fixing them up, and using them as safe houses for unhoused mothers and children. PHA has been trying to track them down, and the other night, Jennifer had stopped PHA’s ancillary police from evicting someone from an occupied home by showing up and screaming at them while streaming on Facebook Live, then calling the police on what she calls the “fake police.” “Everything we were doing to get accountability has been met by resistance and retaliation, so we gotta do some extreme shit,” Jennifer told me with a hoarse laugh.

I asked Jennifer how houselessness is intricately connected to the fight for racial justice. “In Philly, almost all the unhoused people are Black, and they’re brutalized by the police by habit,” she said. “Nobody sees them because we like to pretend they’re not there. But homeless people are the underdogs of this Black Lives Matter movement, and now they’re speaking out. It’s not us speaking out for them—it’s them taking a stand.”

Encampment residents eating a donated lunch of Philly cheesesteaks

As people in the encampment helped themselves to a lunch of Philly cheesesteaks, I took a seat next to a man in his 60s named Rodney, who told me he had been denied public housing because of his criminal record, which stemmed from an arrest for possessing half a pound of weed while driving across state lines to a party. “I lost my federal financial aid for college, and now white boys are making millions,” said Rodney. “The problem with Philly, like every great city, is that black folks came here from the South under the Great Migration, and there was a widespread loss of industry so people were out of work. The rich people have got tax loopholes—it’s the working class who got really fucked. We are getting screwed.”

Philly encampment resident Rodney

Rodney pointed out that Philadelphia is a Democratic stronghold with many prominent Black politicians—but this hasn’t stopped the deeply-entrenched housing corruption and back-room deals that are fueling its houselessness crisis. “You’ve got a lot of black folks in city office, walking around in Armani suits, and they’ll sell their own mothers for a dollar,” Rodney said, spitting into the grass. “They’re all corrupt.”

The sun was starting to set, so I hitched a ride in an activist’s truck to the main camp on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. On the way, he told me some wild stories of houseless people struggling to find shelter during a pandemic. “People whose tents had been swept by the city three or four times eventually went to live in the international terminal of the airport,” he said. “Someone stole a limo, and some other people squatted an airplane.” He pulled up to the camp, which sat on a giant field across from the city’s largest Whole Foods and the pristine Rodin museum.

“This never would have happened without the George Floyd death—they would have swept the camp within a day,” he said. “Cops have only been here one time when there was a stabbing, it’s truly a no-cop zone without being anarchist-flashy.” This zone, in comparison to the family-friendly camp we’d just visited, felt more like a party—speakers were blasting hip-hop, men were sitting in circles playing cards, and all kinds of people were pulling up with donations and other gear.

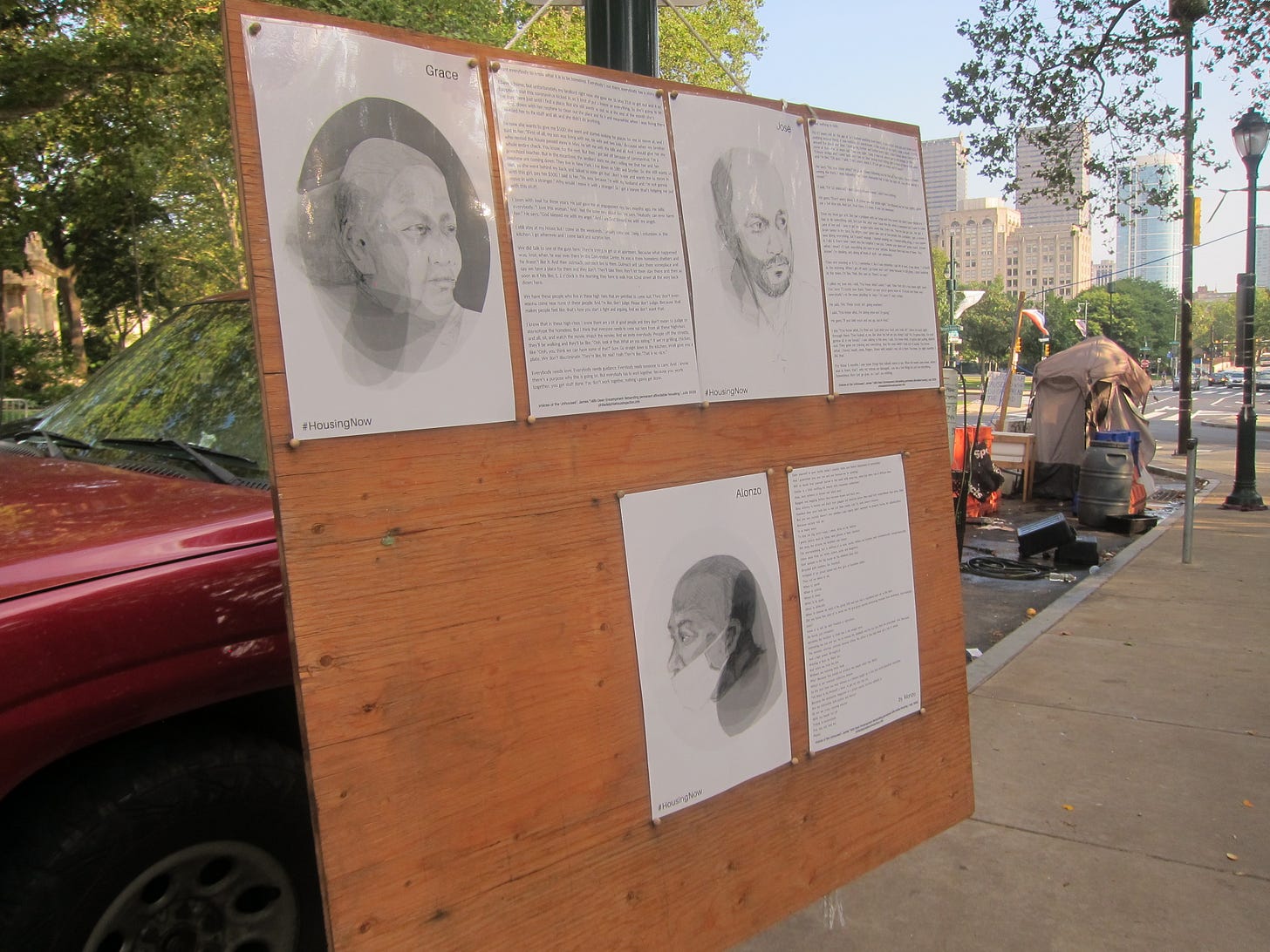

According to the activist, the camp had become a sort of safe space for people with substance abuse issues who can’t stay in shelters because of their no-drugs policies. K-2, a synthetic cannabinoids also known as “spice” that can induce psychosis, is particularly popular because it is technically legal, so it doesn’t show up on pee tests, and you can’t get arrested by cops if caught. As we stood chatting next to a billboard decorated with the photos of various residents, a barefoot woman sauntered up to us. “It’s a revolution!” she hooted, hiking up her shirt to flash her tits, then flopping over and shooting me a lopsided grin, adding—“They told us it wouldn’t be televised.”

As darkness began to set, I wandered over to the food table, past two skater kids slumped over next to a portable speaker, smiling goofily at each other, too strung out to open their eyes. “Would you like me to get you a quiche,” asked a man from behind me, who introduces himself as “Reef.”

When I ask if he’s named after reefer, he smiled, and told me about growing up in foster care in the ghetto before ending up on the streets. Despite being houseless, he’d managed to find employment, at one point sleeping in the stairwell of the casino where he was working. He’d just turned 30. “People have less of a heart for the homeless than the poor,” Reef said. “But give the homeless a chance to live, and a lot of them will be off the streets. In 90 days, I got a job and an ID. I did it.”

Reef outside of his tent

The skater kid had awoken from his reverie, and sauntered up behind us holding a plate of quiche. Reef told me that when Philadelphia’s houselessness protests were first erupting, he’d get on his phone and try to connect with protestors in other cities, to let them know what was going on. Now that it’s quieted down a little, he’s been working a job in telemarketing while hoping that one day in the near future, residents of the encampment will get permanent housing from the city. “It’s a nice vibe here, people are just chilling—sometimes I go to protests, or watch movie nights in the field,” Reef said, gazing over the field, past the movie screen tarp flapping in the wind, towards the sun sinking behind the glimmering silver Whole Foods. “Mostly, we’re just waiting.”

NEW MODELS PODCAST

I recently hopped on my favorite podcast in the metaverse, the Berlin-based New Models, to report live from a protest in New York City. We talked about all the different types of protests I’ve been attending, my frustration with New York nightlife failing to find its place this revolution, why optimism is a Boomer attitude, and so much more. Listen here! (And def follow New Models, you won’t regret it.)