Namaste, bbs!

My idea of a good place is between the front left speaker of a dancefloor and a cabin cradled in the woods. So after spending the summer tearing through New York and LA’s post-vaxx party menageries, I’ve spent the last few weeks hiding in the foothills of Colorado’s Rocky Mountains—shroomin’ and meditating while poking around the local psychedelic scene.

Colorado is one of America’s trippiest states: Denver was the first US city to decriminalize psilocybin in 2019, and activists are currently pushing to expand the law to allow gifting and communal use. Thousands of hippies invaded nearby Boulder in 1968 and never left, flipping the sober city with their psychedelics, and turning it into a 70s counterculture mecca.

These days, Colorado is a crunchy granola trail mix of Gore-Tex mountain bros, New Age intellectuals, and grey-haired hippies noodling on synths in tie-dye. Not gonna lie, it’s also creepily lily-white—at 87% caucasian, it’s giving Get Out! Still there’s no doubt everyone’s here to bathe in nature—the camping stores’ parking lots are full of Subarus (and DMT license plates)… even the trees here look like shrooms!

Today I took a walk up a mountain and came out higher than the trees. Pale Aspens watched with their eerie third eyes as I nibbled on a white albino shroom, pine needles playfully tickling my neck. The decaying summer sun crowned my skull with a radiant halo as charred branches twisted like devil horns to dancing light and shadows. Skin shimmering in the breeze, I sniffed the junipers and thought about what someone told me in New York, when I was lamenting the ego-driven feuds consuming the pandemic rave scene: We eat each other alive because we do stand in front of the ocean to feel our irrelevance.

Colorado has long been where the counterculture goes to tune in and drop out. Drop City, one of the first hippie communes, built solar-powered geodesic domes here out of recycled car metal, and alpaca-raising queer anarchists still hide out in ranches tucked in the Sangre de Cristo mountains. Clearing my mind of clutter and cutting myself off from what Tao Lin called “dominant society” has delivered a much-needed psychic reset. Breathing in this sharp alpine air, I get why Beat poet and Boulder resident Anne Waldman once described Colorado’s landscape as “antithesis reality, antidote to atrocity… a beginning again.” As Waldman put it:

O oxygenated ions

They neutralize free radicals!

Balance nervous system!

Revitalize cell metabolism!

Clear the air!

...

Breathe in the beautiful negative ions of true governance

Breathe out the efficacy of what we may give generously to the world

Drop City hippie commune’s solar-powered domes in Colorado

I was chilling at my hippie friends’ treehouse last week when I noticed a brick university building across the street with a familiar name: Naropa. I Googled and pulled up… my Bloomberg article about psychedelic therapy schools lol. Oh right, now I remember: Naropa is a Buddhist university that launched an MDMA therapist training program last year, in collaboration with MAPS, the organization working with the FDA to legalize medical MDMA.

Naropa’s origin story reads like legend: it was founded in 1974 by Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, an exiled Tibetan tülku and meditation master who helped spread Buddhism in the West. After a chance meeting with Allen Ginsberg while flagging down a New York City taxi (!!!) Trungpa became Ginsbergs’ guru, and invited him and his friends—Beat badasses like Anne Waldman, William S. Burroughs, and Gregory Corso—to establish Naropa’s poetry program, which they named the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics. This school was so disembodied in the beginning that it had no buildings, desks, or blackboards; its classes, according to an ex-student’s memoir, included a seminar from Burroughs where he was required to read secret government reports on UFOs.

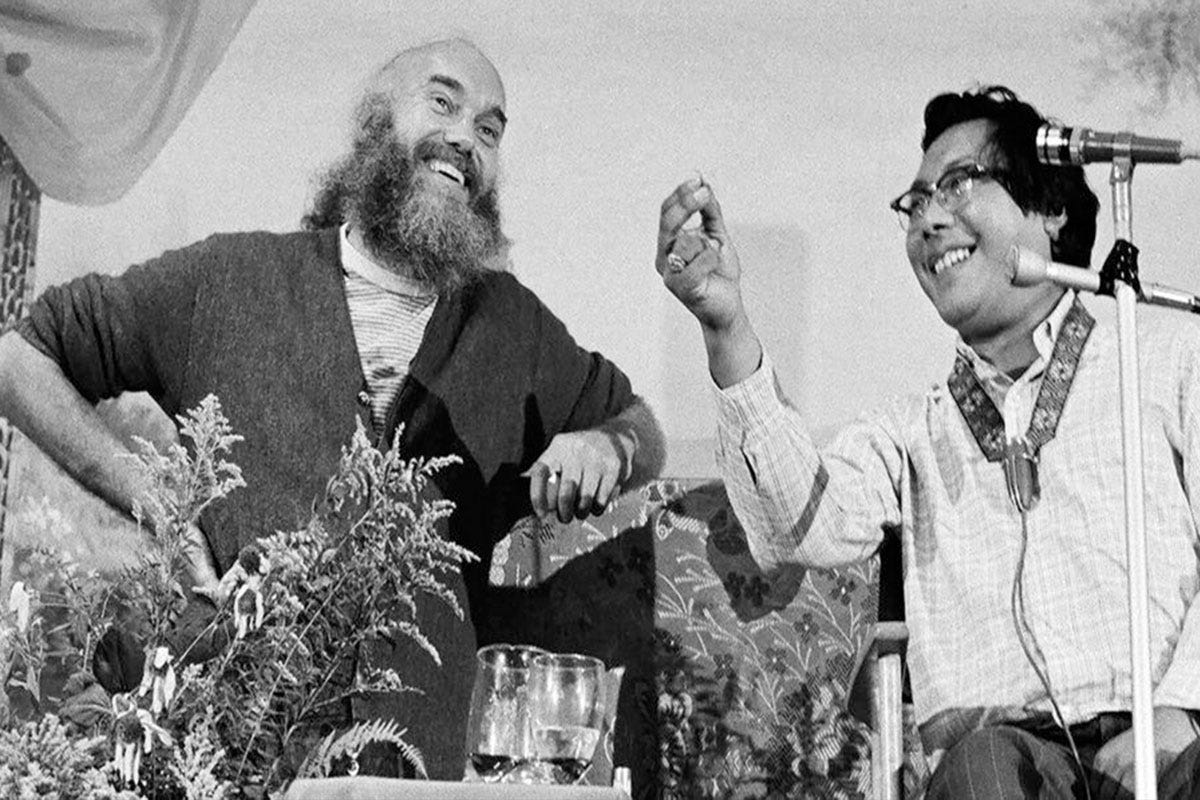

Naropa founder Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche with Ram Dass

Right now, Naropa is one of the only universities in the world where you can earn credits to one day become an official ~molly therapist~ even though medical MDMA isn’t expected to be legalized by the FDA until at least 2023. What intrigued me the most though, was its fusion of Buddhism teachings with MDMA therapy training—not exactly a likely pair. So I set up an interview with Sara Lewis, a Buddhist Psychology and Contemplative Psychotherapy professor who helped to design Naropa’s MDMA course. Sara is also a Fulbright fellow and professional psychotherapist who wrote a book called Spacious Minds: Trauma and Resilience in Tibetan Buddhism.

From my lil mountain and her office at Naropa, our conversation spun around topics like:

the stigma around psychedelics in the spiritual community

how Buddhism and psychedelics offer an alternative to neoliberal concepts of trauma

why MDMA is the perfect medicine for PTSD

Michelle: There’s this huge stigma around using psychedelics within the spiritual community. There’s even a Fifth Precept in Buddhism that says no intoxicants, so it’s like an ideological debate around what’s an ‘intoxicant,’ and how do psychedelics fit into the Buddhist practice. How has this debate evolved since the 60s, especially in recent years with psychedelic legalization and professional psychedelic institutions popping up?

Sara: Even within the Buddhist community there is so much diversity, there isn’t one view. Naropa started as a Buddhist-inspired university and has transformed into engaged activism, meditation, and thinking more broadly in contemplative ways, while contextualizing what our own social identities and being aware of cultural appropriation.

This question of whether Buddhism has become supportive of psychedelics, I’m not sure if that can be answered! Certainly in Buddhist communities, people are asking these questions, discovering the Dharma and their mind through psychedelics simultaneously.

Have you heard this term spiritual bypassing? It refers to how ways we want to circumnavigate around things that are difficult to get to the good stuff. Like bypassing anger, even though anger could be a place of real intelligence. So I think some people really believe psychedelics are spiritual bypassing—you’re creating mystical experiences, but in the end, nothing much changes. Yet, as we know, a psychedelic experience [is often] among the most spiritual experiences of people’s lives, a huge turning point. So I don’t think there’s a lot of agreement.

Would it be fair to characterize that psychedelics were more related to the 60s counterculture’s niche community of Buddhists, and in recent years it’s become more diverse group of Buddhist who are embracing it?

Definitely. There is some crossover: the kinds of people who are born into Buddhist families, and others who come into contact and see it as a religion or set of practices. Both Buddhism and psychedelics have a lot of commonalities. They’re modalities that give us an entryway into the mind and reality. What happens from there? We don’t know. I don’t think meditation is inherently good—it can be harmful, and the same is true for psychedelics.

Psychedelics are empty of inherent nature, to use a Buddhist idea. They can be incredible powerful or harmful. I’ve done research into folks going to ayahuasca ceremonies and developing spiritual emergencies as a result. People are seeking medicines for healing and coming into harm in different ways. There’s great promise and great risk and potential for harm. For this program we’re designing, we care a lot about ethics. Having thought a lot about contemplative practice and chaplaincy programs, we focus a lot on not doing harm and social justice principles.

Was there resistance in getting this program approved at Naropa?

YES. There is still some faculty and administrators who are worried about it. They want to teach serious contemplative practice and psychotherapy, and there’s this idea that psychedelics are frivolous and unsafe. That’s still alive and well. It finally went through because of our students, who are coming to Naropa to train because they specifically want to do psychedelic therapy. Their voices are so persuasive, and there’s a core group of faculty that are interested in this.

How would you explain to these critics that Buddhism can be very synergistic with psychedelics?

There are lots of different ways to do psychedelic assisted therapy. We focus on inner healing intelligence, the same approach as MAPS. That means it’s really important the practitioner not guide or shape the person’s experience, and you’re holding a huge amount of space and allow whatever rises to be seen as having this intelligence. There’s a sense that whatever is arising is fundamentally good or sane. That’s what we’re doing when we sit down on a cushion and meditate. We’re not trying to name certain experiences as good or bad. We allow whatever to rise, and contain that in our experience.

If you’re working with MDMA or psilocybin, these are 8-10 hour sessions. People ask: How can you stay present for that long? It’s not like therapists are sitting there meditating, but you can take this wide view of accepting whatever’s happening and holding that.

In Naropa, we did a collab with MAPS last year, and it was interesting to see the trainees— already licensed therapists and doctors—they had a hard time with this. They said: I think you should bring in internal family systems, or this modality, and it was so hard for people to be able to just allow and witness and be aware of whatever’s arising, instead of trying to make them feel better. That’s the exact opposite of what we want to do. We want to help the person realize they have intense grief coming up, can you allow yourself to experience the wisdom and importance of that grief? Why would you want to take a person’s grief away from them? Meditators are really good at this. [laughs]

Sara Lewis looking radiant :)

There’s been research into how Buddhist mindfulness practices are similar to the brain’s mechanisms on psychedelics. Can you explain this a bit?

There’s a couple studies out there. There’s one for ketamine-assisted therapy, and they found that for people who were already meditation practitioners, it was easier for them to go into Theta-wave state, which is associated with dreaming, meditation, and mystical experiences. It’s like they already carved out a neural pathway. Those people had really positive experiences in ketamine therapy because they were able to work with things like depression and anxiety in that state. Getting into that state occasioned a greater healing potential.

There’s this guy named Richie Davidson at University of Wisconsin Madison who has done a lot of studies with Buddhist monks. In his lab, they’re looking at adept meditators and seeing how it’s like for them on psychedelics. In some ways, I’m like, well duh! Those studies are interesting, but how might that tell us what’s actually helpful for people? Now that we’ve established that psychedelics and meditation help, what’s the connection?

Yeah, like what’s measurable and quantifiable about the brain on psychedelics that relate to the Buddhist concepts of non-attachment, mindfulness… there are almost myths at this point of like, Ram Das giving psychedelics to his Buddhist guru and his guru just like blinks and nothing happens because he’s already so enlightened.

One is this idea of psychological or cognitive flexibility—this concept is really about non-attachment and seeing the emptiness in things, that we create a solid and fixed story. This is really important for trauma, and probably also depression. That’s part of why we’re suffering, we create this fixed narrative. Psychedelics and meditation let us have a bit more space to see things from different angles. Part of my research into meditation, trauma, and resilience has been into Tibetan refugee communities, and I interviewed political prisoners who said, they began to see the prison guard as someone who is a father who needed this job to care for his family, or was a loyal friend. Not saying their trauma is ok, but they have a more spacious and flexible view: I’m seeing it this way but that’s not the whole story. This was my experience and it’s important and there are all these other things happening.

It’s seeing the full story of suffering. I’m hoping there’s more research done into that concept.

I poked into your book and loved it! What was super interesting is how you’re poking holes into this false dichotomy of resilience vs. trauma, and how Buddhism and psychedelics offer an alternative to neoliberal concepts of trauma. I think that’s super needed right now as people evolve their concepts of trauma after the pandemic. Like, pre-pandemic trauma was sort of this stigmatized concept and now… everyone’s traumatized.

Totally!! We typically blame people for trauma and have this idea that someone you weren’t strong enough to cope with trauma and now you’re fragile and in this situation. I think a better way to think about trauma is to look at the structural conditions that created that event, having a traumatic reaction is the natural and healthy response. Our nervous systems are built to protect us—with hyper-vigilance, they’re working too hard. That’s why we have suffering, but it’s also a healthy and adaptive response. I’m interested in the structural conditions that lead to sexual assault, war, violence. Then the Buddhist perspective, the first Noble Truth is that life is suffering. So there’s a lot of paradox: I’m deeply interest in addressing structural inequity, but how do we put that in dialogue with accepting suffering? That paradox is a really healthy and important place to be.

How does MDMA affect how people perceive their suffering? It’s interesting to talk about MDMA as a psychedelic because many people don’t associate it with breakthrough mystical experiences. It’s not a classic psychedelic.

It’s almost the exact right medicine for trauma. I’ve had this question too: why is MDMA so helpful for trauma? It’s related to what we’re talking about. It’s almost like our pain and suffering becomes a way to connect to one another, when usually pain and suffering splits us off from others. I don’t know why, but it does seem to have this effect, of helping us get into contact with our own experience. Because MDMA is so connected to the body as well, if we’re bypassing the body, we’re on the wrong track.

MDMA helps us get into bodily experience of our pain. MDMA allows us to have a wide enough view, where we actually see it as basically good and healthy and wakeful. And it’s almost like, if we could just stay in that place, that’s all we need. It’s hard to stay in that place. But MDMA allows us to do that, and see our rage as healthy and good. See our pain as not something we need to get over and fix, but have this tremendous self-compassion. What happens naturally is we begin to radiate that out and feel connected. All healing is about connection to our bodies, the planet, to our histories, our communities. There’s something about MDMA that allows us to do that.

Do you think that part of the training you’re doing is also equipping therapists to be spiritual caregivers?

What we want is to be helping our clients connect with whatever they themselves are connected to. That’s more important than creating a “spiritual experience.” I’ve been yo ayahuasca ceremonies where there is a lot of cultural appropriation trying to create this spiritual environment, and it’s all coming from the outside, so we want to help our trainees help their clients to access whats meaningful and helpful to them from their communities and lineages. Spirituality can be really different for people. It’s not wanting to bring in too much. Maybe people had traumatic experiences in spiritual communities, so you don’t want to craft something that might be harmful.

How does incorporating Buddhism into psychedelic training differ from other types of therapy training? It’s almost like this minimalist thing of not bringing in too much. Are there challenges for creating these programs?

The thing I’m most worried about is access and accessibility. As you know, these training are so expensive and I’m sure there are some programs that are making giant profits. If they’re done well, they’re really expensive to run because theres so much staff and faculty for close supervision. That’s what I’m most concerned about. We’re fundraising right now for equity scholarships recognizing that BIPOC and other excluded communities have not have equal access. So how are people going to pay for this therapy once it’s legal? If therapists are charging their normal rates for eight hours and multiple sessions, that’s like $10,000 right there. That’s my biggest concern with all of this.

So like, are all the students coming in like, rich professional-class people?

You have to meet the criteria for the MAPS protocol, because all of our trainees coming out will have gone through the MAPS protocol. Those criteria have already been worked out by the FDA and MAPS, they need to already have been licensed. It’s a long list with lots of different types of practitioners. You can be on the pathway to licensure, like graduate students. The only way is to fundraise and Naropa did this for our past training. We gave 20% to people with scholarships. We had therapists from Somalia and Chile who were able to join…

Do you have any Buddhist monks coming through?

Oh my god, I wish! If you know any, send them to us!

Naropa’s next MDMA therapist training program will be announced in the fall, and the price for a 200-hour certificate will be around $10,000, with equity scholarships for historically marginalized groups