Thank you everyone for your sweet texts and tweets about the first half of my interview with Sophie. I know she read this newsletter—especially the posts about drugs and raves—and I looked forward to the post-COVID day when we’d catch up. Transcribing this interview has helped soothe the loss of what will never be, and I’m grateful that it struck a chord.

It’s 2015 and I’m standing on the red carpet at the hottest party in New York City. The PC Music crew—Sophie, AG Cook, QT, GFOTY—spills out of a limo into the rapturous roar of their stans. A scrum of actors pretending to be paparazzi thrust flashing cameras in their faces screaming: “DO YOU DRINK RED BULL?!” (...the party was sponsored by Red Bull lmao) Inside the venue, each saccharine 30-minute set pounds dopamine hits like sledgehammers, the walls bouncing to glistening plastic synths and giddy voices yammering about bloffee (you know, blowjobs and coffee!) Sophie ascends the stage in a PVC jacket and black latex gloves. The audience is a frothing sea of rhinestones, streetwear, and fur. Tonight is about GLAMOR, the mosh pit is a SCENE, everyone is giving SHOWS. We can go crazy and go pop if that’s what you want to do.

I end up by the bar, next to a Very Serious music journalist (straight, white, male, bearded, you know the deal) who mostly writes about house and techno. He dismisses this music, which nobody has a name for yet, as bubblegum drivel too performative and self-conscious to be Very Serious. “I just don’t connect with irony as a musical stance,” he sneers. At the time, this is the dominant stance of most Very Serious music people I interact with and I feel like a dumb girl for defending it. For shouting that I love these songs because—just because they give me a rush like poppers!

Now I wish I’d just said: don’t worry babe, this music is not for you.

+

It’s 2017 and I just moved to LA. I’m spending my nights at Satanic mansion parties surrounded by Scarface piles of ketamine. Hollywood is more decadent and depraved than I’d dreamed. Sophie releases “It’s Okay to Cry,” standing naked and vulnerable in what is unmistakably a Moment. What hits me is a feeling of total gestalt: she has transformed into the pop icon her music has always been about. The reveal sends shockwaves through the scene—everyone I know is texting some version of: omg bitch!!! Sophie is trans!!!, delighting that we can now claim her our queer queen.

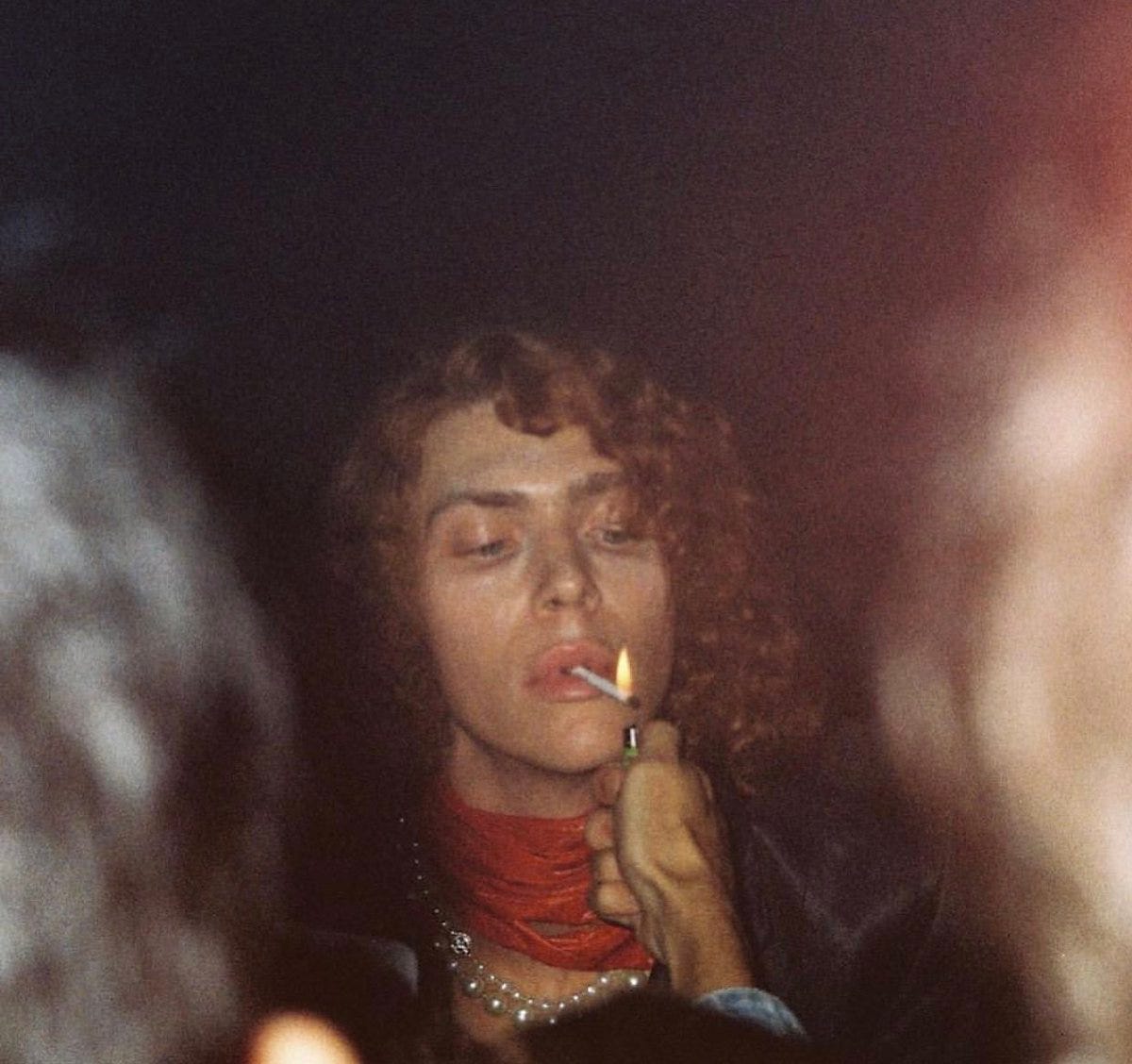

One afternoon, my editor at Teen Vogue sends me to a nondescript diner in Hollywood next to a row of sex shops to interview Sophie. Up until this point, she had shunned press and photographers. I walk in and see her nestled in a booth in the back of the room, wearing a leather jacket with TECHNO scrawled on the sleeve, shrouded in a halo of vape rings. After years of feverish controversy around her work, she tells me it’s time for her to join the conversation. She’s saying: this is who I really am.

+

It’s 2019 and I’m in a seaside town in Crete for a music festival organized by my friend Abyss X. The club looks like an ancient Minoan palace, four crimson red pillars holding up an open thatched roof looking into the starry mountains. The dancefloor is cracking to a spontaneous b2b2b set between Ziur, Nkisi, and Rabit. Under the strobing lights I see flashes of Sophie dancing behind me, boxy Prada blazer hanging off her shoulders, gusts of the night breeze spraying the scent of ocean and pink bougainvillea into our hair.

+

A week later, I’m cruising through the Greek seaside in a convertible with Sophie, her girlfriend, and a couple Greek club kids, scouting locations for a photo shoot. Our photographer, a 19-year-old angel I met at the festival, suddenly tells us to pull over—she’s spotted a picturesque stretch of sand. We spill out onto the black rocks and Sophie wades into the water. She is wearing a white shirt, combat boots, no makeup, so simple. It’s like she didn’t really give a fuck that we’re doing a shoot for Vogue. We spend the rest of the day floating in the waves and eating seafood. The photos come out perfect.

+

It’s midnight in Athens and I’m at a gay club with Sophie and our new Greek friends. Punky queer kids—eyebrows shaved, lips tattooed—sidle up to us to pay tribute, telling her softly how much she’s changed their lives, given them something to aspire to. Sophie smiles beatifically. Then we squeeze into the club to a corner table and the DJ instantly stops playing awful pop remixes and transitions into Sophie songs. Later I ask her what it feels like to hear her own music in a big gay club like that, and she says that in the booming hi-def sound system, she heard things she wants to fix.

+

It’s 2019 and I’m texting Sophie: hi bb I heard you’re in LA, let’s get fucking stoned 😈 She says, I’m in sessions, come bring us some weed?? Drops the address for an Airbnb in Echo Park. When I push through the gate she’s sitting on a sofa with a bunch of musicians, asking them what kind of music they want to make. She was always lifting people up, helping them manifest their visions, seeing their potential for greatness. We smoke a spliff and then she gets up and perches next to her Monomachine. She ekes out a beat in five minutes, then glances up at me with a twinkle in her eye, as if relishing her own quickness. That night I run off early to chase some party. I don’t remember what the party was, but I do remember wishing I’d had a real conversation with Sophie, thinking: next time. It is our final hang.

+

Sophie was here for the girls—the strange Dionysian mermaids feeling restless in our own bodies. I am the icon, she said, I am the dignity and the strength and the illusion. The new American girl. The pop star of your dreams. The golden Hollywood star with her name awaits her in heaven. Rest, queen.

This is part II of my unearthed Sophie interview, which took place in Los Angeles in 2017 and is published here for the first time. Part I is here. There may be a part III… I haven’t decided yet. If you’d like to support this work + stay in the loop, subscribe:

Michelle: I want to play a game with you.

Sophie: Oh cool!

M: What is the most honest sound?

S: Good question. I like the idea of an honest sound. This is a boring answer, actually, but if you’re a musician, the most honest sound you can make is your signature, something that’s developed by you, that’s authentic to you. Something that’s not a preset.

M: What’s your signature sound?

S: A load of the sound design noises that I do. People comment that they can detect my particular sound, the way I process things. It’s almost like a sculptor or painter. Everyone has their own little touch. The closer you can get to that, the more honest the sounds you make are.

M: What’s the saddest sound you’ve ever heard?

S: The sound of my manager telling me that my [Red Bull] concert was cancelled. We were all crying. It was such a sweet bunch of people and we were working so hard as a family unit, living and sleeping together and really getting into the concepts we were putting across in the show. It was very sad to not get that release and get people’s reactions.

M: Aw, please don’t give up! It has to happen—the show must go on.

S: I will do it, and if it’s a reduced version, that will suffice for now and we’ll just move on and keep in mind the full vision of the original intention with it.

M: Let’s go back to the game.

S: I don’t think I’m doing very well at this game but I’m up for trying again.

M: Who is the most perfect pop star?

Good one. Madonna pretty much blows my mind constantly. Because she knows what the fuck she’s talking about. She created the model. She’s just a fucking badass.

M: She is, and people don’t respect that enough sometimes. The amount of hate she’s gotten for aging really pisses me off. Why do you think she’s the perfect pop star? You worked with her right?

S: I did. I don’t think I would say she was the perfect pop star. I mean no one’s perfect, and what makes you perfect is being imperfect, and having integrity over such a long time period, and [laughs] at some points not having integrity, and that being something that you move through. Imperfections make the perfect pop star. Being willing to be imperfect.

M: Who is the most perfect producer?

S: I really respect what Mike Will Made It does. We did a little bit of stuff together as well, and just in those moments, he was so open minded, like a lot of people that I’ve worked with in those worlds. I think being open minded and using your body… if it’s good, it’s not because of academic intellectual reasons, it’s because your body tells you it’s right. You just listen loud and feel the music.

Like the Rihanna team, the way they put music together, it’s the same thing. You’re just feeling it. And I have enormous respect for people who can put that very pure interaction with music and translate that to a global pop star level. Risk-takers, I suppose, I really admire. And I have definitely come across some of them. It’s the most real stuff. And people know that, people feel that. That’s why it becomes some of the best music.

M: What was it like to work with Rihanna?

S: The thing I love about that is I get encouraged to make the weirdest hardest things I can come up with. And… she’s cool. Like, cool people. I’m really happy to see that openness and willingness to take risks exist at the very top tiers. Because it’s more the underlings copyists people that are insecure that don’t do that, and that stuff is not as good. I feel like the very best people working at the top levels, they think about music the same way I did when I knew nothing. Just feeling.

M: How has being in the pop industrial complex, here in Hollywood, working with the biggest pop stars, changed the way you think about pop music?

S: I’ll tell you the interesting thing, is that my experience of doing music in pop contexts has made me realize that it is not about diluting, compromising, generalizing what you do. But actually going further into yourself, to be more yourself, to be more individual. Most people would assume that pop music is going to push you in the other direction, and that your personal or independent music might do the reverse. But my experience, particularly just recently working with some of these people, has been that I need to go further into my weird root individual self completely unaffected by other people, and just push myself to be entirely myself with all that stuff. That’s been my experience and takeaway. And that really inspires me.

M: Is that unique to you, or is that true for everyone in the top tier, you think?

There are a few different types of people, but certainly the best ones, that certainly seems to be their approach. Like DJ Mustard or Mike Will, the Neptunes, Timbaland, all of that. You develop, and are strong in, your own sound and identity and that’s what you put forward. And you actually change things through doing that.

M: Who is your dream collab, dead or alive?

S: I would say Leroy Burgess, who is this singer and producer in the late 70s and 80s who worked on this blue beat sound that’s related to the disco, early electro, and funk worlds. He had a band called Logg. His songs meant so much to me and my friends growing up. And he’s still around, he’s doing concerts. And I don’t know how we stumbled on it in the first place, but it was definitely my thing. He’s someone I’d really like to do a track with.

M: Were there other disco or funk records that you’d cite as influences? Disco is not necessarily what I’d expect you to cite.

S: Often like, a lot of people say J-pop or kawaii [in reference to my work], but the energy of that stuff is rooted in disco music and the original New York and Chicago electronic music innovators. And Detroit, obviously. Moving that into electronics is very much what I’m trying to access, the way that moved out of disco and what that culture meant.

My friend Jeffrey, who you just met, is very much present in that disco world and it’s very much alive and has meaning to people. I’m inspired by that energy and what that culture meant, but I’m aware that we exist in different worlds, and I’m trying to imagine what the music sounds like that is positive and liberating and weird and dark and real and trying to imagine what that could be in the current day. So I would definitely say that stuff I’ve done is modern disco music. It takes more the attitude of those things, but tries to bring the sound world forward. It’s not what people would call “nu disco,” which misses the point completely for me. It misses the point of what was authentic and original about that music. Cause it’s not about sound. It’s about the ideas and the energy of it.

M: Which ideas from disco are inspiring to you?

S: The ideas of dancing and uplifting people. Giving people a new feeling that makes them feel alive in the time and feel connected and liberates people. Talks about real things, relevant things, and also acknowledges a sense of humor. That’s really what the best artwork does. It has light and dark.

M: You know, I always thought disco was too cheesy for me, like, I’m such a techno slut— until a few years ago, when I went to a party in a bumper car arcade in Coney Island by DJ Nicky Siano, and as I was twirling around in the dark — on acid — surrounded by all these Paradise Garage heads, it clicked. I was like, I get it.

S: Well you know, techno evolved from disco. It took the essence of what was the atmosphere in those clubs. Early stuff like Larry Heard mixes, it was fucking wild. Like, Frankie Knuckles would have the sound of trains running around the quadrilateral speaker systems that they had in these clubs. And these machines had just been invented, the early acid and Roland machines. They were making drum tracks, swirling all of these sound effects like that. That crossover point of where disco and the first house music was first being created—it had soul and meaning and was new. Genuinely new. That’s what musicians should be doing. Trying to work out what that feeling means now. What that intention could be right now. And it’s not what it was then. That’s the puzzle that you’re trying to work out with music, I feel.

M: That reminds me of that last time I was at Berghain, and I was talking to the bouncer, who was this Black guy with a really strong New York accent. And I was like, “Wait! You’re from New York?” He was like, “Yeah I am, but I’ve been living in Berlin for the last two decades.” And he used to work for Paradise Garage too. He was like, “The old Berghain, before it became a playground for tourists, was the closest thing to Paradise Garage that I can remember.” And I thought that was really cool because on the surface those clubs don’t seem similar at all—but in fact, they both captured the same essential feelings… of being on the edge of culture.

S: Berghain is definitely the most authentic club experience I’ve ever had. Even though people say it’s changing, it’s still beyond what you experience at other clubs, and I hope it continues to exist like that.

M: Speaking of Larry Heard’s sound design, I’m working on another piece right now about CDJs and how they changed the way people play music. I was thinking about this idea of smoothness and continuity, but with CDJs because you’re able to break apart music in this really quantized manner, hyper-detailed way…

S: I still can’t work that out, by the way. I don’t know how CDJs work, really. I cannot figure it out. I still do it like vinyl.

M: Well just in terms of looping and…

S: I know what you mean, it allows you to do faster transitions and throw shit on top of each other that would be hard to match by ear. And a lot of the ways New York DJs operate, it’s really representative of how that technology informs us, and how that’s represented right now. I have a lot of respect for people like that. It’s awesome, it feels like the way it should be done right now.

M: I was talking to M.E.S.H. and he was making this argument that you can’t say old electronic music wasn’t as disjointed and fractured as now. Because Larry Heard and Frankie Knuckles were doing crazy shit as well.

S: Was he talking about that as well?

M: Yeah!

S: That’s interesting. Yeah, totally. I think around the same time as prog trance or whatever that was, it became about mixing smoothly between one turntable and another, and in key, and it became like “learn to DJ!” around the time those academies started popping up. I feel the same way about production. Learning to produce in the proper way. I don’t know how useful that is, really.

M: Well it’s boring to think about learning to do things perfectly because machines can do that even better.

S: I feel the same way about the vinyl argument. Yeah vinyl has a certain sound, but it’s not as high fidelity as a WAV or whatever. There’s a lot of nostalgia of people holding on to their ideas—it goes back to what we were talking about the difference between artificial and real. I think there’s a lot of things flipped completely the wrong way about what’s real and what’s artificial. Obviously, being an all-vinyl DJ or whatever, I don’t know how real that is. It seems to be more about an illusion of authenticity or something. Or pretension or whatever. Yet that’s perceived as more real than modern pop tracks. Those things definitely need to be shaken up and questioned a bit. Get straightened out a bit.

M: We’ve talked about how your work connects to the energy and culture of disco music, but do you think it’s fair to discuss your work in terms of critical frameworks like accelerationism and the new sincerity movement?

S: To be honest, I don’t really think in those terms. I’m a musician, producer, and artist, not a critical theorist. And I find it easier to express myself that way.

M: I think the new sincerity thing resonated with me because music journalists often label your music as “ironic.” And it doesn’t seem to me like irony is the dominant mode, but can also be a useful tool sometimes.

S: I think probably that gets confused with acknowledging that things exist.

M: Hah ok. Well I just have one or two last questions, I promise.

S: No honestly, I enjoy talking about all of this, and talking with you, it’s really an honor.

M: So tell me, why did you decide to talk now [after being anonymous for so long]? Why contextualize this work?

S: No I’m not. [long pause] I think it’s more that, firstly I felt like it. Secondly, I think it’s more that people are more willing to engage with me on the terms that I want them to. I didn’t want to enter things out of a standard, a norm, a normal way of approaching things. I’ve always, in the past, had the approach where I’ll say something when I’ve got something to say. And now I’m talking to people, the way in the past I’ve talked to people when I’ve put things out, or whatever. I don’t really see a difference between what I’m doing now and what I’ve done in the past. It may seem different to other people, but I don’t really see a difference. I also think it can be limiting to pigeonhole and box yourself in, and say my music is about this, when you’re initially doing it. I suppose I was more willing to let people say what they thought the music was about. I think we’ve heard a fair amount of what people think it’s about. So now I want to join the conversation a little bit.

M: I think people are responding to it really well, and it feels like maybe we’re seeing you for the first time. Not that we weren’t before. But there’s a directness and visibility now.

S: Yeah, the thing is like, in terms of the video, I certainly feel more happy presenting myself. I feel like I’ve been able to do some of the things I’ve wanted to do, with some of the people I respect, and I’ve communicated myself through my music quite effectively because it’s led me to these situations where I’m living here now and having these experiences that I wanted to have. I’m working with a diverse group of people that I respect. Learning. Giving myself the opportunities to access and learn from these people. But I still feel it’s about the ideas I’m interested in, it’s not really about me.

M: It makes me happy that you’re happy presenting yourself more publicly. It strikes me that even when you’re “exposing” yourself — both literally in your latest music video, and figuratively, stepping out from behind the curtain — I feel like there’s still a sense of mystery about you. There’s always gonna be an element of performance and the unknown.

S: And that’s the case for everyone. Even for the person who is on Instagram every two minutes. Doesn’t mean that person is being more or less genuine. I don’t know… I’m having fun. I’m enjoying what I’m doing.

M: Is the desire not to be pigeonholed, why your publicist said you didn’t want to talk about your… coming out?

S: I don’t really agree with the term “coming out.” I don’t use that to describe myself, particularly right now, I don’t see that as the case at all. I want to talk about the things that are relevant and interesting to me, rather the focus be on those things, to be honest. The rest I just think it is what it is, let people be who they want to be.

M: Is it kind of like, how female DJs hate talking about being ‘female DJs’ because that ends up being the whole conversation?

S: Yes, it’s exactly that. I speak to a lot of friends about that. People are who they are. They want to talk about what they do and their interests and have the focus be on that. They want to be viewed as artists, not under any other category.

M: Also in today’s #MeToo climate…

S: What does that mean, Me Too?

M: The #MeToo thing that’s all over on social media right now with sexual assault? The idea of visibility and speaking out, owning your own narrative, and coming out with your truth is a very important idea to people right now.

S: It is, if it’s the truth that you want to put forward. It’s not anyone’s business for anyone to project on to you.

M: I guess this is where I have to ask about the whole gender appropriation thing that people were bringing up a few years ago. I was talking about it with my friend recently, and he was saying he thinks it’s bullshit because when you try to police gender, you’re reinforcing this idea of binaries, that a certain music or aesthetic is considered ‘feminine,’ when there is no such thing. So that’s the difference between gender and cultural appropriation, which is a real thing, and people are bringing that mentality towards gender when you end up reinforcing binaries that shouldn’t be there. Do you agree with that?

S: I do. I suppose it depends on the individual. I found it difficult to accept the things put forward there and the things people have said. [sighs] Yeah. It’s all a conversation. I’ve received some thoughtful apologies from people. The only thing you can do is go about the thing that you do with integrity according to your beliefs.

M: I think it’s a lesson that sometimes the things you say, even maybe with good intention, can end up sounding kind of TERFy.

S: The opposite intention of actually being really hurtful. Yes. That’s true but it’s not my vibe to call people out. Because I speak through my music, and that’s all I need. If it takes longer to address the people, then that’s fine. And if it doesn’t connect with them at all, that’s also fine. That’s the mode I choose to express myself, and I feel I express myself clearly through those things.

M: That’s very sweet. Because I think a lesser person would feel very validated in calling people out and being angry and proving people wrong. Even your tweet after the LA show was cancelled was very generous.

S: My friends were texting me like, “I’m distraught, I’m devastated” but I can’t imagine what people must think in these other situations where there’s been a natural disaster or it’s been an attack or something.

M: Like Mykki Blanco in Russia.

S: Right. I can’t imagine how that must feel. This is a case of a concert being cancelled out of my control. But people being attacked and killed at concerts, that’s happened. And I can only imagine it puts things in perspective a bit. So I felt it was important to say it’s devastating but it could have been a lot worse and you have to be grateful for that.

M: Let’s go back to “It’s Okay to Cry.” Is this song the introduction to the rest of your album, like setting the tone?

S: It has a pretty clear message and sound, and is consistent with the rest of the material, but they don’t have the same tone. The tone of the album is very varied. It’s like that problem with like, those music services which take one song and give you another that sounds exactly like it, as if you only want to listen to music that sounds exactly the same. What you really want to do is listen to music that has the same intentions and integrity behind it.

M: What was the thought process behind your hand gestures and motions in the music video?

S: When you’re just showing a bust, the hands become important because you’re operating in the frame of a screen.

M: But why only show the top? Why did you want to have this disembodied feeling in space?

S: I dont think it’s disembodied, I think it’s like you’re having a conversation face-to-face with someone. You lose that if you’re further back. You do get to see more of the body at the end, at different angles. It shows just enough. It’s like us having a conversation now, you can’t see my legs. We’re communicating through our eyes and voices. I wanted it to be more conversational.

M: Have you seen the Madonna '“Ray of Light” video? It has a very similar vibe.

S: I think there’s something fundamental about that. The Sinead O Connor video is a classic as well. When you’re talking about direct communication, which is my main focus in my music, you can’t get much better than that: face to face emoting, one take. All of those things help you. Basically the whole video is one take.

M: Wait, sorry, detour real quick: have you seen this movie Victoria? You have to watch it, I’m obsessed. One take movie, set in Berlin, where you follow this girl on one night out. It’s one of the only movies that captures the stupidity and the euphoria and depravity that can happen in one night. It’s my favorite clubbing movie right now, and it was also done in one take.

S: Wow I love that. But I have to say, I don’t like watching films. I don’t have the attention span for it. It’s weird saying that in Hollywood now but I’m getting better.

M: What was the green screen footage behind you in the music video?

S: That was a long conversation. What we ended up with was exactly what we wanted. It communicates itself clearly: a rainbow, a thunderstorm, a galaxy. Everyone knows what that is. It was really a conversation about how we could get that feeling of a shifting sky, which really narrates the emotional journey of a song. It was just a case of sourcing the various bits that had the right ingredients there and tying them together to make a narrative.

M: Wait, you say everyone knows what these symbols mean, and a rainbow seems obvious, but what about a galaxy?

S: I mean people know what the stars look like, they know what that is. It’s direct. It’s not something abstract.

M: Oh, but it kind of is abstract too. Which is probably what I love most about your work: that it always contains multiple contradictions that seem to collapse binaries.

S I love that. What you just said is really comforting and feels great to me. Thank you.

M: Oh good, I’m so happy. Is that something you think about: this… ambiguity between two opposing things?

S: What’s opposing to you?

M: The idea of like, artifice and authenticity - pop and experimentalism - physicality and virtuality - visibility and invisibility - appearance and representation. All of these binaries that you’re collapsing.

S: Wow. Yes. And I think that’s what’s difficult for people. People do think in binaries, that’s how we understand things. When you confuse what those are for people, they’re like well this is wrong. But it’s really important. I don’t know why I’ve given myself this task of: this is what I’m here to do. But absolutely there is such a concise way of putting that, I really appreciate that. I think that’s what people misunderstand. That it’s OK to like techno and pop music. And see what’s good and bad about both of those things. They’re not a boundary. Breaking down binaries seems like an important thing to do.

Incredible

Stunning, thank you so much for sharing this <3